Students participate in pep-up gathering for gaokao in Boluo Secondary School, Huizhou, Guangdong Province on June 6, 2018. [Photo: Lin Jiefeng]

17 hours and 16 minutes. That is all. And six hours must be allocated for sleep. For the first time in her life, Zhang Lijuan grows such an extreme parsimony that she’d calculate every single second to make sure there is enough time for her hasty cramming. Tomorrow morning, Zhang, along with 9.75 million teenagers all over China, will face the challenge of the gaokao, a national examination that can decisively change their life direction.

For the past three years, Zhang had been studying 14 hours a day, with only three days off every month. Her desk has been covered with countless textbooks and references, her teenage life filled only with study. Even on the final day before gaokao, she still reviews notes during her lunch break, memorizing as many facts and formulas as possible.

“I’ve been focusing on one thing and one thing only: getting accepted into one of China's top universities. This is a battle I cannot afford to lose,” said Zhang.

An annual occurrence, gaokao is the sole determinant for admission to Chinese universities. The test result will decide what universities an examinee can attend, and consequently, determine whether he or she will find a well-paid job in the future. About three in five students will make the cut in this silent battle, while only one out of 20 can access the top universities in China.

As ruthless as it sounds, gaokao is now close at hand. Over the next two days, people’s conventional perception of China being a boisterous and vivifying country will be totally shattered. The whole nation will be immersed in tranquility, expectation and anxiety, with anxiety dominating, only for this solemn examination.

The roulette of fate

Family members of candidates for the national college entrance exam wait outside the exam site at the Lhasa Middle School in Lhasa, capital of southwest China's Tibet autonomous region, on June 7, 2013. [Photo/Xinhua]

Driving south from Yinchuan, the capital of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, the earth takes on a brownish hue. Zhang, alone with her parents and two siblings, lives in Xihaigu, an arid region that is elusive on a map, but stands as a colloquial term for “poverty and barrenness.” Declared “uninhabitable” for humans by the United Nations in 1982, the world’s least fertile land is where Zhang’s dreams grow.

With an annual income of less than 30,000 RMB ($4690), Zhang’s family are unable to support all of their children in dreams of going to university. Her two sisters quit their studies after middle school, leaving the only hope of seeing the outside world to the family’s youngest member.

“I have never been outside of Ningxia…my life is made up of cave houses and barren lands. I want to see the world outside, and the only way to fulfil my dream is to pass gaokao and get a good job in a bigger city,” said Zhang.

From 1977 to 2016, 120 million Chinese students enrolled in universities. The roulette of fate has fundamentally changed poor students’ lives, and Zhang wishes to be one of them.

“In my hometown, many girls would drop out of school at a very young age and then be a peasant their whole life. I don’t want my life to be like that,” Zhang added.

Agreeing with Zhang, Cui Shuang, a secondary school teacher from Huizhou, Guangdong Province, noted that for teenagers like Zhang, gaokao is their life savior.

“As an English teacher in a small town, I believe gaokao is the fairest and one of the only possible ways to a better life for students from poor families or even ordinary ones in small cities, despite its score-oriented nature and the fierce competition,” Cui Shuang added.

The desire to be a master of one's own fate has led to exorbitant self-discipline. In Zhang’s class, where all 40 students are from rural areas, many have been taking extreme measures to beat the odds. One of Zhang’s classmates has even resorted to scalding her own arms with burning incense, so that she can stay awake for longer to do more exercises.

And the exam does not discriminate due to family background. In mega cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, many teenagers have participated in extracurricular cram schools to optimize their scores.

“Most of my classmates have signed up for Olympic Math Training courses, which our parents believe can help us get bonuses in the gaokao. I have to do the same, though I am not interested,” said Chen Lin, a Shanghai-based high school student. He also noted that his parents have bought him tonics and oxygen generators, in hopes of improving his concentration.

“Gaokao is the first social selection of elites that happens in our life, of course no one wants to be labeled as a failure,” Chen added.

New alternatives

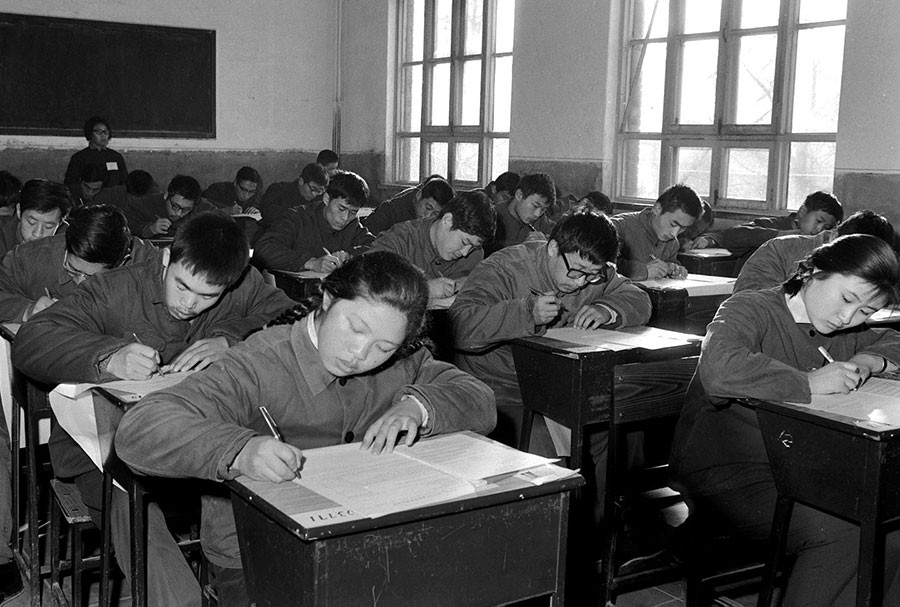

Beijing students take the restored gaokao in 1977. [Photo/Xinhua]

China may be changing at mind-blowing speed, but worship of the gaokao remains as immutable as when it was first initiated in 1952. As an ancient Chinese saying goes: scholarship pursuing surmounts all other occupation, and such traditional perception still holds true in the new era.

But in recent years, the academic ritual has been gradually losing its glamor due to its overemphasis on grades and cramming methods. Chinese authorities have already initiated plans to reform the gaokao and its enrollment system by 2020, providing more places in universities for students from rural areas, as well as building more vocational schools as alternatives to the nation’s higher education.

“Attending vocational schools used to be discriminated, but the situation is changing gradually. For poor students who cannot get into universities, vocational schools have provided them a chance to get out of poverty,” said Ma Jinming, a vocational school student from Xihaigu region.

A gaokao banner signed by students. [Photo: Yu Yonghua]

Meanwhile, overseas study has also become a new way to avoid the gaokao. According to Xinhua, nearly 610,000 Chinese students attended schools and colleges overseas in 2017, an increase of 11.7 percent compared to that in 2016.

In Chen’s school, prep classes are provided for students who wish to get their bachelor’s degree abroad, but the cost is extreme. Such curricula are based on the U.S. education system, while the students may take trips to the U.S. annually.

“At one time, gaokao was regarded as an authority to select students, but now we can have the freedom to choose it or forsake it, to some extent, this is a great progress,” said Chen.

Award-winning photos show poverty reduction achievements in NE China's Jilin province

Award-winning photos show poverty reduction achievements in NE China's Jilin province People dance to greet advent of New Year in Ameiqituo Town, Guizhou

People dance to greet advent of New Year in Ameiqituo Town, Guizhou Fire brigade in Shanghai holds group wedding

Fire brigade in Shanghai holds group wedding Tourists enjoy ice sculptures in Datan Town, north China

Tourists enjoy ice sculptures in Datan Town, north China Sunset scenery of Dayan Pagoda in Xi'an

Sunset scenery of Dayan Pagoda in Xi'an Tourists have fun at scenic spot in Nanlong Town, NW China

Tourists have fun at scenic spot in Nanlong Town, NW China Harbin attracts tourists by making best use of ice in winter

Harbin attracts tourists by making best use of ice in winter In pics: FIS Alpine Ski Women's World Cup Slalom

In pics: FIS Alpine Ski Women's World Cup Slalom Black-necked cranes rest at reservoir in Lhunzhub County, Lhasa

Black-necked cranes rest at reservoir in Lhunzhub County, Lhasa China's FAST telescope will be available to foreign scientists in April

China's FAST telescope will be available to foreign scientists in April