Carving out a symbol of virtue

Editor's note: Traditional arts and crafts are supreme examples of Chinese cultural heritage. China Daily publishes this series to show how master artisans are using dedication and innovation to inject new life into heritage. In this installment, we find out how the craftsmanship of jade carving still thrives in modern times.

A jadeite miniature of Taishan Mountain, majestic yet intricately detailed, faithfully conveys the grandeur of the spot that has captivated ancient Chinese emperors and literati of the past and today. The mountain located in East China's Shandong province was not only a symbol of the pinnacle of feudal power in ancient times, but also an inexhaustible source of inspiration for those holding the pen. Tang Dynasty (618-907) poet Du Fu once wrote, "Nature's wonders in divine chime. Day and night, they slice time."

Such ingenious workmanship of nature has found its inheritance in this massive man-made jadeite piece on permanent display at the Chinese Traditional Culture Museum in Beijing.

The essence of the jadeite's texture and the exquisite craftsmanship of jade carving run parallel in this masterpiece.

From the east the sun rises, splitting the cloud-enveloped mountain into the sunlit side and the shaded side. Verdant woods shelter the flowing water, bridges and winding trails, where 64 figures, nine deer, nine cranes, and three goats find joy and peace.

Major scenic spots of Taishan Mountain are vividly adapted to this miniature.

Jade artisans have made full use of the raw stone's original shape, veining, and color.

The light green part was carved into the sunlit side, with economical strokes to resemble the sheer cliffs while presenting the jadeite's natural beauty.

The shaded side, however, displays a darker bluish-gray color. This is where Du's poem is inscribed, above which two gliding cranes enjoy the sun.

Both the glowing sun and the cranes are skillfully made from impurities in the jade stone. The technique qiaose dates back to the Shang Dynasty (c.16th century-11th century BC) and is one of the most commonly applied methods in jade carving to reflect the artisans' ingenuity.

A miniature Taishan Mountain is among the four jadeite "national treasures" housed at the Chinese Traditional Culture Museum in Beijing. (Wang Jing/China Daily)

This miniature Taishan Mountain is among the four jadeite ornaments housed at the museum that are dubbed "national treasures". Produced in the 1980s, they took more than 40 Beijing-based jade artisans eight years to complete, according to museum guide Yang Yuwei.

From these pieces, the delicacy, complexity, and diversity of jade caving — a time-honored craftsmanship — are fully revealed.

Chinese people have a long-lasting attachment to jade, which probably accounts for their continuous drive to improve the craftsmanship of jade carving.

From the around 9,000-year-old Xiaonanshan site of Northeast China's Heilongjiang province, archaeologists have excavated more than 200 pieces of jade ware, the earliest known in China.

Exquisite jade ornaments and vessels of various sizes, shapes, and textures have also been found in subsequent relic sites across the country or passed down through history, exhibiting aesthetics and ritual significance and symbolizing wealth and social status.

Above all, jade has always been associated with human virtue — gentleness, inclusiveness, integrity, resilience, and purity, to name a few — and the efforts taken to maximize the charm of the stone are frequently compared to the polishing of people's fine character.

A household rhyme goes, "Jade, if not refined, will not become a useful ware. A person, if not learn, will not understand the principles of life."

The main procedures of jade carving, handed down throughout thousands of years, include qie (cutting), cuo (grinding), zhuo (carving) and mo (polishing).

These four Chinese characters form a commonly used phrase meaning exchanging ideas while mutually learning, and pondering on a specific problem over and over again — an apt metaphor of the long journey to become a jade-carving master.

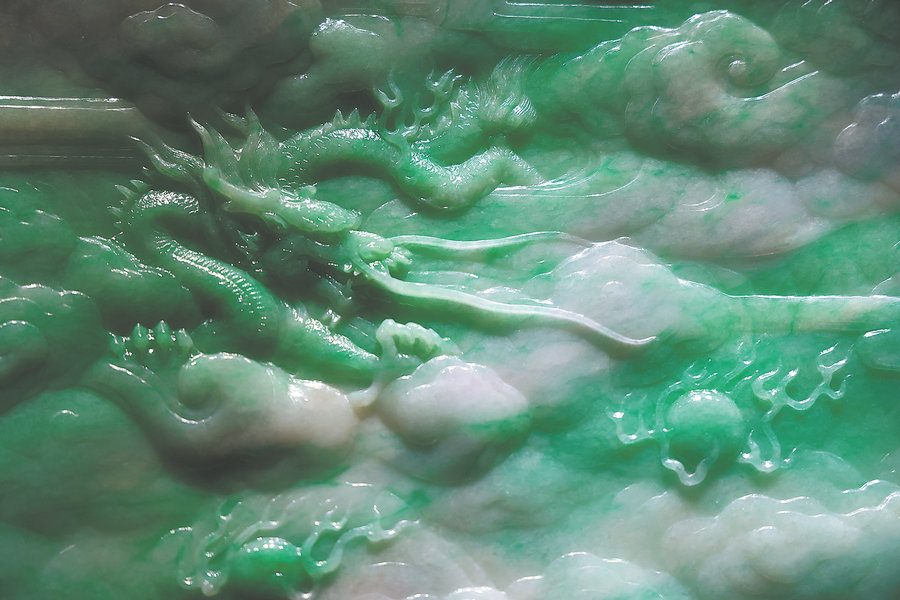

One of the nine dragons writhing in the sea of clouds that adorn a jadeite relief screen at the museum. (Wang Jing/China Daily)

Pursuit of perfection

Upon getting a raw stone, craftsmen would first examine and cut out the flawed or cracked parts before designing according to the original shape of the remaining part.

For a highly skilled, demanding artisan, this crucial initial step can be very consuming.

Yu Ting, a 51-year-old jade carver from Suzhou in East China's Jiangsu province, is renowned for his expertise in crafting jade utensils as thin as eggshells. He recalls a time when he acquired a 260-kilogram raw stone, of which only 49 kg was of the purest quality. With this portion, he skillfully fashioned a 10-piece dinnerware set weighing a mere 368 grams, in addition to crafting another pair of bowls and a teapot.

Since high-quality jade is truly rare, the improvement of skill always comes with the pursuit of realizing the material's potential to the extreme while compensating for the jade's natural imperfections or even taking advantage of them — qiaose is simply one of these techniques.

Another piece of the "national treasures" is an extravagantly decorated vessel for perfuming. The jade artisans managed to build this 71-centimeter-tall vessel in the shape of a giant two-eared cup out of a raw stone only 65 cm in height, using a technique called taoliao.

To manage this, they scooped within the main body to carve out the lid. Within the lid, they applied the same method to further carve out the base. These independent parts were screwed together using carved spiral ridges.

On the perfuming vessel are relief patterns of auspicious beasts from ancient Chinese mythology, as well as nine three-dimensional dragons tightly gripping the ears and the lid, with 10 loops dangling from carved decorations.

Chain carving, a craft with a history of more than 3,000 years, is without doubt the highlight of the third piece — a jadeite flower basket. Its hoop handle on the top and two movable chains, each with 32 interlocked loops, almost double the height of the original stone.

According to Yang, the museum guide, its raw stone has many cracks and flaws. When carving the chains, the artisans searched for a relatively fine part of the jadeite, which they twisted in and out multiple times to expand its form.

A jadeite vessel at the Chinese Traditional Culture Museum. (Wang Jing/China Daily)

Jade-carving master Dong Wenzhong, who played a major role in producing these four pieces, told China Daily shortly after their completion in December 1989 that chain carving was the most challenging part of this basket.

They had to be extremely careful to avoid flaws in the jadeite; and once the chain broke, they could never repair it — using adhesives to fix broken jade is considered dishonest by jade carvers, he said.

The leftover materials after carving out the hollow basket were turned into a dozen flowers — peony, chrysanthemum, Chinese rose, plum blossom, and magnolia, among others — and put back into the basket, interwoven and well-balanced.

Nine dark green dragons writhing in the sea of apple-green and opal white clouds, powerful and unrestrained, are depicted on a relief screen that is only 1.8 cm thick, their claws, horns, and beards vividly detailed.

This fourth piece is made of the best-quality jadeite among these "national treasures", whose materials stem from one raw stone, Yang says.

Before carving, the artisans cut this lustrous material piece into four slabs and assembled them into this unprecedented large jadeite screen that is 146 cm wide and 74 cm tall.

The long, yellowish-brown impurities of the jadeite are cleverly hidden, integrated into the image of the jet of water a dragon spits out and lightning released by another hitting the clouds with its claws.

The glowing sun and a pair of cranes on the miniature Taishan Mountain. (Wang Jing/China Daily)

Manual work

In the past, jade carving was much more labor-consuming. Artisans had to sit for a long time at a table-like iron rotary machine with cutter bars.

Summer or winter, they treadled to drive the machine while picking up abrasive sands — usually made from quartz or garnet — from a tray of water.

It was largely by this machine they cut, carved, drilled, and polished to create miracles on the tough mineral that has long been favored by the Chinese.

Since the 1960s, motor-powered rotary machines have been introduced to the industry, along with improved tools such as various grinding heads, cutters, ultrasonic drilling equipment, mechanized grinding beads, and vibratory polishers, Wang Mingying and Shi Guanghai, both from the China University of Geosciences in Beijing, wrote in a 2020 article on the evolution of Chinese jade-carving craftsmanship.

According to them, computer numerical control and three-dimensional scanning devices have been increasingly applied in jade carving. However, detailed manual work, such as that used to make eggshell-thin jade vessels, as well as the above-mentioned qiaose and chain carving techniques, cannot be achieved with these machines.

Yang Xi, a Suzhou-based national-level intangible cultural heritage inheritor of jade carving, has observed this trend. He says it's quite usual for the younger generation to complete the majority of work with a computer and then continue the carving and polishing by hand.

He admits that sometimes even industry insiders cannot tell whether artworks are made by hand or with the assistance of machines.

However, the 60-year-old veteran carver sticks to the traditional manual craft and particularly emphasizes the importance and challenge of originality in design.

Yang Xi is well-known for his series of works inspired by his hometown, a water town with the typical Jiangnan (the region south of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River) temperament.

He has also created various works in which he has inserted new expressions into antique craftsmanship, such as incorporating an internal structure of a mechanical watch into a piece of work — a rare theme in jade carving — and an innovative adaptation of the Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva (Thousand-Hand Bodhisattva).

"The art should always keep pace with the times," he says.

Photos

Related Stories

- Art exhibition held aboard China's Tiangong space station, and in Beijing, Macao

- Jade prospers as vanguard of civilization

- Young art restorer finds his calling on social media

- Trending in China | An inside look at ancient hand warmers

- Guangzhou's Bai'etan Greater Bay Area Art Center becomes new cultural landmark

Copyright © 2024 People's Daily Online. All Rights Reserved.