Ecoprotection efforts boost Inner Mongolia

An aerial view of Ma'anshan village in Harqin Banner, Chifeng city, Inner Mongolia, in September. LIU LEI/XINHUA

Safeguards and subsidies are bringing new life to the grassland.

Despite a summer drought, villager Zheng Jie recently made 5,600 yuan ($780) by selling his Amur grapes. Even in late September, he was busy harvesting his corn and millet fields.

The 59-year-old is also a forest ranger, responsible for patrolling 33.33 hectares of woodland in Ma'anshan village in North China's Inner Mongolia autonomous region.

With its forest coverage rate reaching 90 percent, the village provides a fine example of the integrated efforts being made to protect the beautiful scenery of this grassland-rich region in China's northern border area.

Better lives

At the hilly Tuhum township, Horqin Right Wing Front Banner, the grassland has been divided into small square grids that form a unique landscape.

"The grids are weed blocks and the grass inside has been grown by artificial seeding," said Burensain, a township law enforcement official, who like many members of the Mongolian ethnic group only uses one name.

In May last year, Tuhum launched a grassland restoration project, which had 9 million yuan of investment and combined natural restoration with manual intervention to treat 4,000 hectares of degraded grassland.

Monitoring data show that the grassland vegetation coverage of the banner — whose status is equivalent to a county — rose by 28.67 percentage points from 2016 to last year. The water quality of its rivers has reached Category III standard, or good quality, according to China's five-tier quality classification method for surface water.

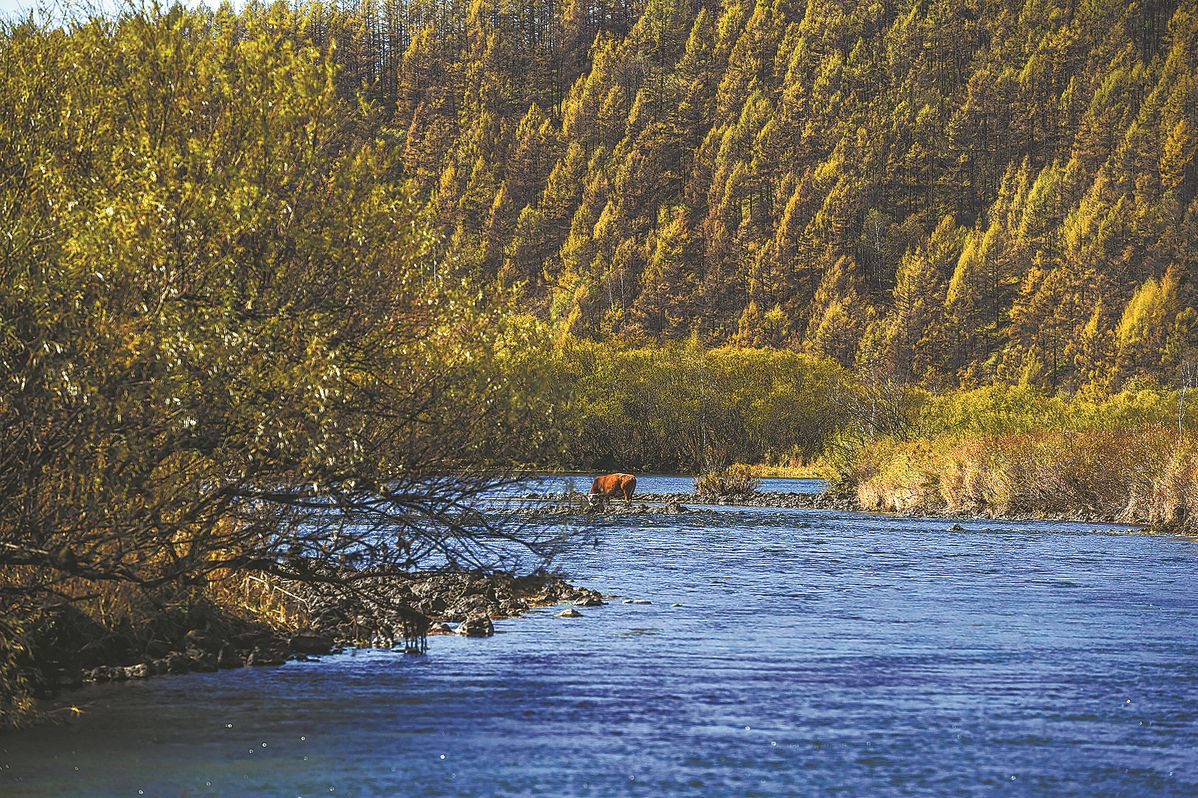

Cattle and horses forage on the Ulan Mod grassland in Horqin Right Wing Front Banner, Hinggan League, Inner Mongolia, in September. LIU LEI/XINHUA

In the banner's Ulanmod grassland, scattered flocks of cattle and sheep graze on river banks and hillsides. According to the local grassland-livestock balance policy, 1.06 hectares of grassland are needed to breed one sheep and 5.3 hectares for each head of cattle. Herders receive an annual subsidy of about 4 yuan for every 666 square meters of contracted grassland.

"We have been living here for generations. Only by protecting the grassland well can we have a better life," said Sarengowa, a herder. She raises about 100 head of cattle and nearly 700 sheep on the grassland, but the number is half what it was in the past.

Having hired two shepherds, Sarengowa devotes her attention to a 33-square-meter dairy workshop she recently opened in cooperation with four other households.

"We produce traditional dairy products such as milk curd, yogurt and cheese to raise the herdsmen's sources of income," she said.

In years gone by, large swathes of grassland in the region suffered from desertification and salinization due to overgrazing, drought and other factors.

"When spring came, there would be a severe sandstorm lasting several days, leaving sand under the doors and on the windowsills," recalled Bai Jiranbayar, a herder in the banner's Hadabuqi village.

Hadabuqi is in the hinterland of the Horqin sandy area, China's second-largest sandy area, which covers more than 660,000 hectares. More than 86 percent lies in Inner Mongolia, with the rest in neighboring Jilin and Liaoning provinces.

In 2017, the banner implemented a complete ban on grazing. As a result of a poverty reduction policy, Bai Jiranbayar's family left their shabby clay house and moved into a newly built brick home funded by the government. Bai Jiranbayar began raising cattle in a shed.

As part of the efforts to restore decertified land, 100 hectares of sea buckthorn, planted three years ago, has grown 1 meter tall. Bai Jiranbayar is now one of the rangers for the sea buckthorn trees.

Jin Jalgaa, Party chief of the village, said the environmental benefits of the sea buckthorn forest have already become apparent, and the financial benefits will become clear next year, when the sea buckthorn fruit is harvested.

So far, 90 percent of the sandy land in the banner has been restored.

Over the past decade, Inner Mongolia has planted millions of hectares of trees and grass, which has seen the area of decertified land reduced continuously, according to local government statistics.

The Arxan National Forest Park in Arxan, Hinggan League, North China's Inner Mongolia autonomous region, in September. PENG YUAN/XINHUA

Cleaner environment

In an area near Ulan Suhai Lake, Liu Xiuzhen, a farmer in Sainhudag village, Urad Front Banner, usually does her morning exercises to the rhythm of music or takes a walk with other village women.

"The air is good," said the 51-year-old, whose house has been renovated with new furniture and pot plants. A few years ago, though, the environment was not so livable.

"The environment around the lake has improved a lot, so we decided to renovate the house. Years ago, the environment was so bad that we wanted to move away," she said.

According to Liu, the lake water was once brown and smelly. "Now, the water is clear, and there are more fish and birds. Swan geese, which had not appeared here for decades, were seen overwintering at the lake last year," she said.

The change is largely the result of the treatment of pollution on farmland around the lake. For years, the excessive use of fertilizers was a key factor in lake pollution.

"We manage the farmland on our own, but the environment belongs to everyone. We must protect our farmland," Liu said.

On her farm, she changed her crop from corn to wheat and used farmyard manure and artificial weeding, but no plastic film, in response to government measures to reduce agricultural pollution.

She receives government subsidies for the adjustments, and her wheat has been recognized as a pollution-free product, which sells at a higher price than ordinary wheat.

With all of these changes, Liu's income rose by 40,000 yuan last year. She said she hoped green products will be further promoted so more farmers around the lake area will adopt the environmentally friendly farming model.

Intensive reform measures have also delivered tangible outcomes in other places that were once badly polluted.

At the foot of the Helan Mountain section in Alshaa, a prefecture-level area, the vegetation is lush, with a few rock sheep occasionally running by. Locals say that snow leopards — a rarity in the area — have also been spotted recently.

Poor protection efforts during decades of coal mining, as well as overgrazing in the mountainous area, led to environmental degradation. Since 2016, local authorities have shut down 57 coal-washing plants and 67 mine shafts, while launching vegetation cultivation in mining areas.

"The environmental protection measures at Helan Mountain are good. Compared with 20 years ago, the edge of the forest has moved forward by 5 to 10 meters," said Li Dong, an official with the administration of the Inner Mongolia Helan Mountain Nature Reserve.

Last year, the proportion of days with good air in Inner Mongolia was 3.7 percentage points above that in 2015, while the proportion of sections of surface water with good water quality under national assessment was 22.9 percentage points higher than in 2016, according to official data.

A view of the Shenjunwan tourist resort in Ulanhot city, Inner Mongolia, in July. WU XILIANG/XINHUA

'Gold mountains'

Ma'anshan, where forest ranger Zheng Jie lives, is thriving, with local people engaged in planting grapes, greening and tourism. A village tourist reception center is also currently under construction.

"The hills were bare, and heavy rain led to floods, with stones washed down," said Zhang Guozhi, the village's former Party chief, recalling the scene from over 10 years ago.

The village authorities encouraged residents to plant trees, guaranteeing them a financial return. So far, the village has completed the greening of some 200 hectares of mountainous land.

In addition to tourism, the locals receive an income from mountain-grown products such as hazelnuts, mushrooms and apricots.

The village, which has over 1,000 residents, shook off poverty in 2017. Its per capita disposable income reached 15,900 yuan last year.

"We will continue our greening efforts and aim to become a 5A-level scenic area," said Liu Yeyang, the current Party chief of the village.

Like Ma'anshan, the integration of agriculture and tourism has also been practiced in other rural areas.

In Gaogenyingzi village, near the urban area of the city of Ulanhot, an old section of riverbed that was used as a garbage dump has been transformed into a water park, the Shenjunwan Ecological Experience. Dozens of villagers work in the scenic area as security guards, cleaners or boat pilots.

"Several years ago, the site was quite smelly. Who would have thought that an abandoned sand pit would become a 'treasure bowl'?" said Peng Dianqi, a villager who is head of the security staff in the scenic area.

He earns 4,500 yuan a month from the job. "I used to be too poor to eat properly or buy clothes. Now, I can't say that I'm rich, but I'm living a really comfortable life," said Peng, as he praised the policy that has brought about major changes in his life.

According to the managers of the tourist area, new projects will be carried out in the future to develop winter tourism and family inns so the value of the beautiful area will be further realized.

A swan takes off from Ulan Suhai Lake in Inner Mongolia in 2020. LIAN ZHEN/XINHUA

Living off the forests

In the Bei'an Forest Farm in the Dahinggan Mountains in the city of Genhe, Inner Mongolia, forest rangers are busy digging pits for tree-planting efforts in the spring.

"Environmental protection is our job now," said Zhou Yizhe, a worker on the forest farm. In 2015, a ban on commercial logging in natural forests was implemented in the area, so workers like Zhou became rangers employed to cultivate trees.

The 58-year-old will retire in two years' time. He said he hoped more young people will be recruited to the forest farms so that they will take up the baton of preserving the vast forests.

Many former forest workers like Zhou are now responsible for the daily protection of forested areas.

Zhou Changhe, 71, was a maintenance worker for the trains that carried wood at a forest farm in Arxan, a city in the southwest of the Dahinggan Mountains.

"When the train tracks were dismantled due to the logging ban, I was worried that there would be nothing to do. But it is everyone's responsibility to protect the forests for future generations and maintain the ecological balance," said Zhou, who moved into a six-story building in 2017, having lived in a small bungalow for decades.

Whenever he visits the mountains for fun, the retired forest worker often reminds people not to start fires, and tells those digging for wild vegetables not to root out the plants. His family also values the harmony between humans and nature, and between people, he said.

In the neat living room of his new first-floor home, a plaque hangs on the wall bearing Chinese characters that read, "Harmony in a family makes everything successful." His wife Zhou Xiurong enjoys square dancing with her peers.

In Arxan, about 60 percent of the population make a living through tourism-related services.

Jiang Huixin, whose ranger father was also a logger, cherishes his job at the Arxan National Forest Park, where he is in charge of tourist safety and vegetation protection. He always teaches his 5-year-old son to protect nature whenever they go outside.

"I often tell him that flowers and trees are all living things. We should take care of them," said the 31-year-old, who earns about 3,700 yuan a month. His wife works in the park's catering sector.

"We still live off the forests, but in a different way. Tourism has developed due to the forests and natural beauty, and life is better," Jiang said.

Photos

Related Stories

- China's Inner Mongolia sees foreign trade up 19.6 pct in January-October

- Amazing Ulansuhai Nur ecological restoration project

- In pics: autumn scenery of Arxan city in Inner Mongolia

- Inner Mongolia expands telecom networks in vast forests of Greater Hinggan Mountains

- Picturesque autumn scenery in Inner Mongolia

- Foreign trade of China's Inner Mongolia up 20.4 pct in Jan-Aug

Copyright © 2022 People's Daily Online. All Rights Reserved.