China ensures safety of underwater cultural relics with technological means

After taking a 91-meter-long escalator into the water, crossing a 146-meter-long horizontal corridor, and walking into a viewing gallery which is 40 meters below the surface of the Yangtze River, visitors find themselves at the Baiheliang Underwater Museum (or the Underwater Museum of White Crane Ridge), located in the middle of the Yangtze River in southwest China’s Chongqing municipality.

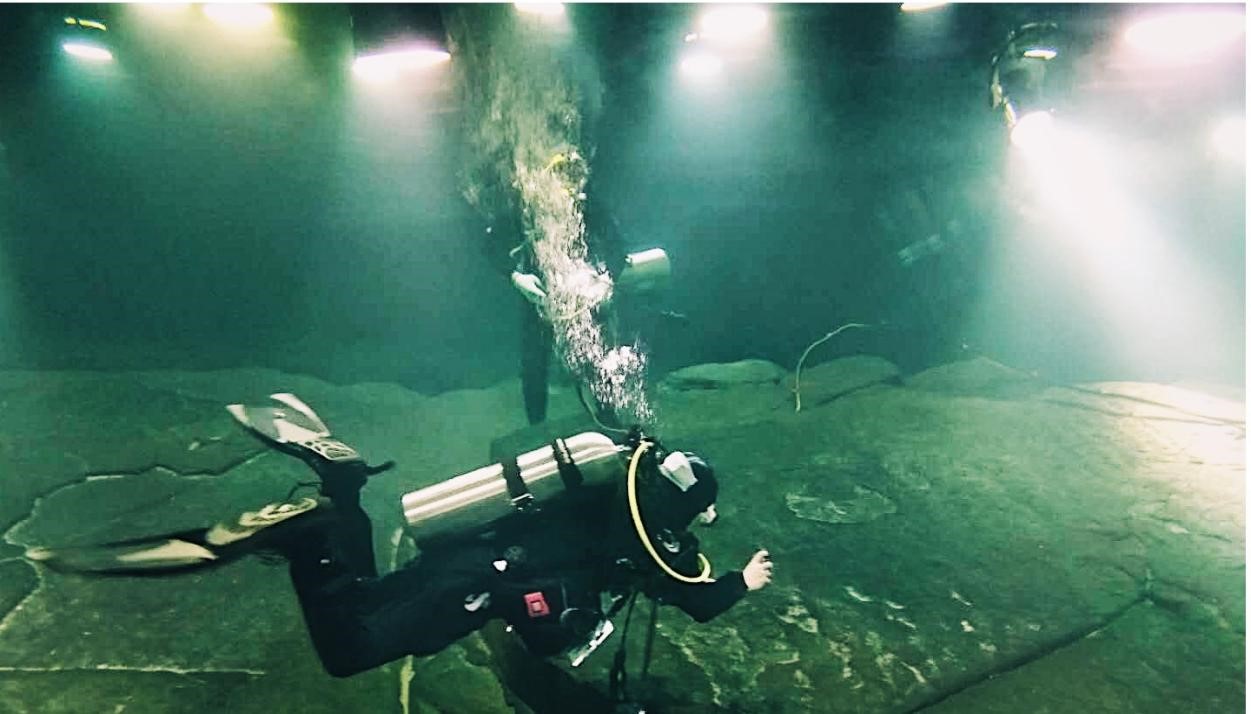

A diver carries out underwater tasks at the Baiheliang Underwater Museum located in the middle of the Yangtze River, southwest China’s Chongqing municipality. (Photo/Baiheliang Underwater Museum)

Involving a total investment of 193 million yuan ($30 million), the underwater museum built in 2009 is hailed as the world’s first underwater museum that visitors can access without having to dive by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

The underwater museum was built upon a natural stone ridge, which is 1,600 meters long and 15 meters wide. Situated at the intersection of the Yangtze River and its tributary Wujiang River, in Fuling district, Chongqing, the stone ridge was an ancient hydrometric station that used stone fish carvings to measure the water levels of the Yangtze River during dry seasons.

There are now 165 paragraphs of inscriptions on the ridge, which record the hydrological data about the Yangtze River during dry years in more than 1,200 years since the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and a large number of authentic calligraphy works of famous poets and artists and have extremely important hydrological scientific value. The ridge is therefore known as the world’s earliest hydrometric station in the world.

Through the 23 round glass windows of the underwater museum, visitors can see clearly the inscriptions and fish carvings created by ancient Chinese people on the ridge.

The inscriptions on the stone ridge at the Baiheliang Underwater Museum located in the middle of the Yangtze River, southwest China’s Chongqing municipality. (Photo/Baiheliang Underwater Museum)

As the ridge could be submerged in water forever when the Three Gorges Reservoir along the Yangtze River achieves the annual target of storing water at 175 meters above sea level (The target was first met in 2010), a Baiheliang in-situ protection project was initiated in 2003.

The project is the most difficult and technologically demanding and involves the most investment among projects for the protection of cultural relics in the Three Gorges Dam area. It adopted a “pressure-free container” method to realize in-situ preservation of these underwater cultural relics. A huge container was built at tens of meters below the water surface to envelop the core part of the inscriptions on the ridge. To ensure the container is “pressure-free”, its inside is also filled with water.

At the entrance of the viewing gallery of the underwater museum, two professionally qualified divers were preparing to dive into the water to clean the “pressure-free container”.

Since the water gets colder with depth, divers need to dress warmly inside the wetsuit. They also add weights around the waist to control their buoyancy in water. After carefully checking the air tightness of the diving gear, the divers jumped into the diving chamber.

“Every three months, poor water transparency, algal blooms, the growth of biofilms on the surface of the inscriptions and other problems occur within the ‘pressure-free container’. So we need to ask professional divers to clean it regularly,” said Yang Bangde, curator of the Baiheliang Underwater Museum.

While swimming back and forth in the closed glass container, divers open the sewer backup valve so that the sewage hose can remove the sediment in the protection container by the pressure difference between the inside and outside of the container, and wipe the algae from the glass widows and decorative lights.

The deeper they dive, the greater the water pressure becomes and the harder it is for them to carry out tasks. Therefore, each diver usually work no longer than one hour each time, and must wait at least 24 hours before performing another underwater task.

A stone carving of fish on the ridge at the Baiheliang Underwater Museum located in the middle of the Yangtze River, southwest China’s Chongqing municipality. (Photo/Baiheliang Underwater Museum)

The temperatures and materials of underwater lights could affect the water quality, according to Yang. The staff members of the museum have therefore constantly renewed the deep water lighting system.

They changed the materials of lamps from aluminum to stainless steel so as to reduce the matters produced by long-term immersion of aluminum lamps in deep water, and replaced warm white lamp beads with cool white ones, effectively reducing the temperature of the water and slowing down the growth rate of algae. Besides, they have employed a filtration and circulation system that operates ceaselessly. “The water inside the protection container is even less turbid than potable mineral water,” Yang pointed out.

“As a proverb in Fuling goes, ‘The sighting of the stone fish carvings promises a good harvest,’” Yang said, pointing to carp carvings on the ridge.

Over 1,200 years ago, after careful observation of the water level of the Yangtze River, local people found that once the stone fish carvings emerged from the water, it meant that the low-water level days were gone and a year with adequate rainfalls and a bumper harvest was to come. As far as Yang is concerned, the inscriptions on the stone ridge are like a book hidden underwater that has recorded a history of more than a thousand years.

The viewing gallery of the Baiheliang Underwater Museum located in the middle of the Yangtze River, southwest China’s Chongqing municipality. (Photo/Baiheliang Underwater Museum)

Photos

Related Stories

- Precious cultural relics displayed in Chongqing

- Chinese museums enter metaverse to make better use of nation’s cultural relics

- Ruins of China's earliest state academy found in east China

- China to step up protection, utilization of grotto temples

- Tibet uses sci-tech mechanism for cultural relics protection

- In pics: cultural relics and art section at CIIE

- China pledges to promote cultural relics protection through sci-tech methods

- Repair work conducted on flood-damaged cultural relics in Taiyuan, Shanxi

- Cultural relics in Inner Mongolia Museum reveal exchange and coexistence of cultures in the ancient past

- China retrieves 58,000 relics in law enforcement campaign

Copyright © 2022 People's Daily Online. All Rights Reserved.