11 years on, Fukushima morass still poses danger

On March 11, 2011, the meltdown of three nuclear reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Japan became the world's second-worst nuclear disaster after the plant was hit by a tsunami following a strong earthquake.

The International Atomic Energy Agency classified it as a Level 7 nuclear accident, which means it had widespread health and environmental impacts. The world's only other Level 7 accident was at Chernobyl in Ukraine, then part of the Soviet Union, on April 26, 1986.

Nearly 165,000 residents were evacuated from Fukushima and surrounding suburbs, but most have been allowed to return after 10 years of decontamination. It is estimated that fewer than 30,000 do not intend to return.

Little progress has been made on the most pivotal and hardest work of decommissioning the Fukushima Daiichi power plant-how to remove the nuclear residue from the meltdown. The plant owner, Tokyo Electric Power Co, has said it could take another 30 years to retrieve undamaged fuel, remove resolidified melted fuel debris, disassemble the reactors and dispose of contaminated cooling water.

The International Research Institute for Nuclear Decommissioning of Japan estimated that the nuclear waste mix from melted fuel rods and other materials in pressure vessels that melted during the accident could weigh as much as 880 metric tons.

Hiroaki Koide, a retired researcher at Kyoto University, said the Japanese government and Tokyo Electric Power Co's 30-40 year plan for decommissioning the reactors could not be achieved because it would be "impossible even in 100 years" to remove the large amount of scattered nuclear debris, which would have to be sealed in a "sarcophagus".

Moreover, 11 years after the disaster, the reactors at Fukushima are still being cooled down, said associate professor Nigel Marks of the physics and astronomy department at Curtin University, Western Australia.

"And this will continue for many years to come. A vast number of large storage tanks have been built on the site, but space is rapidly running out."

Despite resistance from locals and neighboring countries, the Japanese government is sticking with its decision in April last year to discharge the nuclear contaminated water into the sea starting in spring next year. About 1 million tons of radioactive wastewater, now stored in 1,000 tanks on the site, was used to cool the reactors and contains radioactive cesium, strontium, tritium and other radioactive substances.

The Japanese government and Tokyo Electric Power Co said the Advanced Liquid Processing System, a multi-nuclide removal system, can remove 62 radioactive substances except tritium, which is difficult to remove from water.

Professor Brendan Kennedy of the School of Chemistry at the University of Sydney said: "Tritium is all around us, but now we have an excess. The question is what to do with it."

At the invitation of Japan, an investigation team of the International Atomic Energy Agency visited Japan last month to complete its first field investigation.

Lydie Evrard, deputy director-general of the agency, said the government invited the agency to conduct a safety review, hoping that it would give basic policy support to the treatment plan.

Photos

Traditional tie-dye products of Buyi ethnic group in Guizhou popular among tourists

Traditional tie-dye products of Buyi ethnic group in Guizhou popular among tourists Girls from mountainous areas in Hainan pursue football dreams

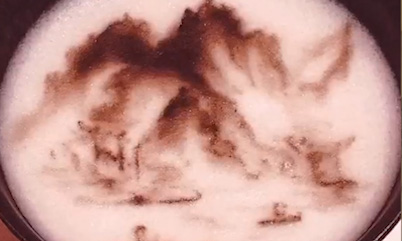

Girls from mountainous areas in Hainan pursue football dreams Chinese artist forms elaborate images using whisked tea foam in revival of Song Dynasty’s cultural splendor

Chinese artist forms elaborate images using whisked tea foam in revival of Song Dynasty’s cultural splendor Wild lilies in full bloom as snow melts in Xinjiang

Wild lilies in full bloom as snow melts in Xinjiang

Related Stories

- Japan's highest court orders TEPCO to pay damages to Fukushima disaster victims

- Seven questions the Japanese government must answer on its decision to discharge nuclear wastewater into sea

- China backs ROK's call for int'l organizations to cooperate on Fukushima issue

- Iconic Japanese artwork turns into satirical symbol over Japan's nuclear wastewater dumping

- Commentary: Chernobyl disaster, a contemporary reminder

Copyright © 2022 People's Daily Online. All Rights Reserved.