Journey of faith: meeting Xinjiang’s Muslims

Id Kah Mosque in Kashgar is the biggest mosque in Northwest China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. (Global Times / Fan Lingzhi)

The icon of Kashgar for almost six centuries, the Id Kah Mosque stands out in silhouette. Solemnity and magnificence oozes through every crack of its 140 emerald pillars, while the weathered green carpets leading to the mihrab bear the imprint of time and footprints of pilgrims.

It was five in the afternoon. In a small room concealed behind a resplendent niche, 48-year-old Abbas Nurmemet, who has served as a khateeb (prayer leader) for 26 years, quietly changed his clothes to prepare to host the daily religious ritual. In the mosque’s spacious courtyard, 61-year-old Memet Sawut was happily chatting with his friends. This is a place full of celestial dignity, but one that also ripples with terrestrial joy.

The largest and most influential Islamic shrine in Xinjiang, the Id Kah Mosque, is not only a religious site but also a harbor of many interlinked, overlapping cultures and layered identities. The green domes swirl and reverberate with the murmurs of prayers, while art enthusiasts are awestruck by the mosque’s Arab-style minarets and Chinese furnishing. It is a hybrid building of mixed people who defy the narrow categorizations that belong in the sectarian religious legends and nationalist narratives of later times.

“I feel relieved when praying in the mosque. It gives me inner peace and offers me a place to share life stories with my friends. I can feel genuine happiness here,” said Memet Sawut.

Den of bigotry, lighthouse of faith

48-year-old Abbas Nurmemet, who has been serving as a khateeb (prayer leader) for 26 years. This is his fifth year as Id Kah Mosque’s khateeb (People’s Daily Online/ Kou Jie)

The Id Kah Mosque is well-known as a holy place, but a few years ago it was the site of appalling blasphemy and bloody violence. In 2014, Juma Tahir, the then imam of Id Kah, was stabbed to death by three Islamic extremists outside the mosque, the same spot where his predecessor narrowly survived a knife attack in 1996.

According to incomplete statistics, from 1990 to 2016, several thousand violent terrorist acts were carried out by ethnic separatists and religious extremists in Xinjiang. In 2014, the year when Juma Tahir was brutally killed, a total of 1,588 violent and terrorist groups were taken out, 12,995 violent terrorists arrested and 2,052 explosive devices seized.

“That was a time of fear and turbulence. Islam is supposed to be a religion of peace and love, but the religious extremists made our belief so sectarian that it excluded any other,” said Nurmemet.

Distorted religious thoughts have heavily affected the local people’s daily lives. 34-year-old NurEhmet Abdula, who now runs a home decoration company, was then a victim of extreme thoughts. Doing business with a religious extremist in 2015, he was brainwashed by his business partner into thinking that women were inferior to men and should stay home, and that a true Muslim’s duty was to “expunge the taint of other faiths while commandeering their traditions.”

Abdula’s wife, 30-year-old Sudman UbulEsen, was a nurse. She was forced by her husband to stay home for over two years and was not allowed to wear make-up or to talk to any strangers. Even worse, she was verbally abused and threatened by her husband, which has left her greatly traumatized.

“I was shocked when my husband asked me to give up my job and become a prisoner of housework. I was an educated woman with a promising career, but for the sake of our little daughter, I had to accept this unfair treatment, and that was a nightmare,” said UbulEsen.

Extreme thoughts also put Abdula’s business in jeopardy. He refused to do business with people who are not Uygur, and his unpredictable temper drove all his clients and employees away. He even became a preacher of such thoughts, leading to fierce objection and criticism from his family members.

“I grow up in a Muslim family. What my husband told me was totally against my religious upbringing. Two years of suffering have made me realize that a good religion should never shackle humanity, while religious extremism will always try to manipulate people, urging them to harm others,” said UbulEsen.

“Ignorance and detachment from society are the major reasons why religious extremism is accepted by many people. Religion should evolve with time, and Muslims should be knowledgeable so that they cannot be easily manipulated,” said Nurmemet.

In the years that followed Tahir’s tragic death, the Id Kah Mosque has become not only a religious site, but also a shrine of knowledge for its believers. Religious classics such as the Koran and Selections from Al-Sahih Muhammad Ibn-Ismail al-Bukhari are translated by scholars into Mandarin Chinese, as well as the Uygur, Kazak and Kirghiz languages, providing convenience for religious believers of all ethnic groups seeking to acquire orthodox religious knowledge. Several libraries have also been built in the mosque’s courtyard, while local Muslims are encouraged to read books in various fields including science, technology, society and law between their prayers. Countless religious scholars, historians, poets and writers have been studying or doing research in the mosque, providing intellectual support for the eradication of religious extremism in Xinjiang.

“It is only by understanding the peaceful essence of Islam and learning modern knowledge that a Muslim avoids the temptation to see his religion through the obsessions of the religious-ethnic prejudice. The mosque should not only be a religious site, but also a distribution center for knowledge,” said Nurmemet.

Giving up religious extreme thoughts, Abdula starts a new life with his wife UbulEsen. Though the damage has been done and scars remain, the couple decide to let bygones by bygones, and live a new life as both modern citizens and traditional Muslims. (People’s Daily Online/ Kou Jie)

Abdula, who was persuaded by his brothers and wife to join a local vocational education and training center in 2018, studied law, Mandarin and took business courses. His thoughts fundamentally changed months after he began his studies, which he believed was a “life-changing experience.”

“By learning Mandarin, I can now easily communicate with my Han clients. Modern management skills have helped me restart my business, and by taking law courses, I have realized how close I was to committing crimes. Being a religious extremist has cost me everything, and I felt so ashamed of treating my wife so horribly,” said Abdula.

Two years after leaving her beloved job, UbulEsen finally returned to her hospital in 2018. Though she can never forget what her husband had done to her, she decided to forgive him, as he had been “influenced by extreme thoughts, and after all he is a nice person.”

“We are still Muslims, we still go to our mosques to pray. But with modern knowledge and better understanding of our religion, I will never be affected by those horrible thoughts anymore, and I want to make it up to my family by being a good husband and a good father,” said Abdula.

Seven years after the imam’s death, the once blood-soaked mosque is now filled with joyful tourists and peaceful prayers. Three years after Abdula gave up his extreme thoughts, he designed and built a small garden filled with roses for his wife, while his company is now back on track, earning him 200,000 yuan per year.

Celestial and terrestrial harmony

Serving as the mosque's Imam for over four years, Abdurusul Shemshidi can now switch easily between his celestial and terrestrial identities. (People’s Daily Online/ Kou Jie)

Five hundred kilometers east of the Id Kah Mosque, several locals began to file into the Ujmilik Mosque, a small community mosque in Hotan, to begin their daily prayers. Although religious, political and media interest have fed on each other to put Uygur Muslims’ lives under more intense scrutiny than ever before, for 50-year-old Abdurusul Shemshidi, this is just another typical day.

Born into a Muslim family, Shemshidi is an expert in Islam. Ujmilik Mosque has over 150 frequent visitors, who voted for him to become their Imam. Religious figures in Hotan, like Abdurusul, often have several loyalties to different identities, the human equivalent of Hotan's layers of dust and stone. Some of them are farmers, some construction workers, and others are merchants. For Abdurusul, his terrestrial occupation is a taxi driver.

After finishing his shift as a taxi driver, Shemshidi quietly changes his clothes to prepare to host the upcoming religious ritual. Serving as the mosque's Imam for over four years, he can now switch easily between his celestial and terrestrial identities.

"Our religion teaches us that living in the moment is very important. Only a happy and affluent person can provide help to others, and that's what I have been doing – to live a better life while following my religion," said Abdurusul.

Abdurusul's biggest pride is his son, who is now studying law in Xinjiang Science and Information Vocational College. He believes that as a modern Muslim, it is important to learn about sciences, law and society, as well as balancing celestial and terrestrial life.

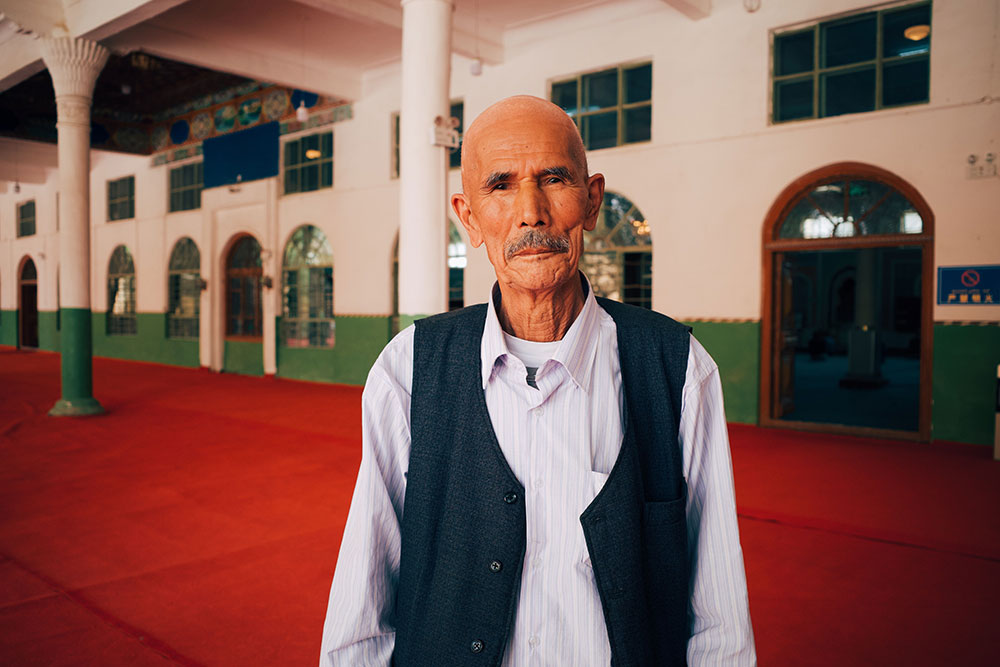

78-year-old Kadir Yusup has been praying in the Ujmilik Mosque for over two decades. (People’s Daily Online/ Kou Jie)

"Religion is only a part of my life. I have many other priorities in my life, such as family and work. It is not hard to find a balance between my religious duties and daily life, as they are closely connected," he added.

78-year-old Kadir Yusup has been praying in the Ujmilik Mosque for over two decades. His apartment is three kilometres from the mosque. Every day after sending his grandson to school, he likes to take a bus to visit the mosque so that he can spend some quality time with his Muslim friends.

"The mosque has changed significantly over the past 20 years. Everything is new. This is the nearest mosque to my apartment, and it has become my daily routine to come here and talk with my friends. Life is getting better, and religion has added some colors to my life," said Kadir.

"Muslims and non-Muslims should not discriminate against each other and should live in harmony, while people of different backgrounds should help each other. This is what a good life looks like to me," said Kadir.

Photos

Zhongwei in NW China's Ningxia enhances desert tourism experiences

Zhongwei in NW China's Ningxia enhances desert tourism experiences Inheritor promotes Shidiao woodcarving in SW China's Xizang

Inheritor promotes Shidiao woodcarving in SW China's Xizang Villagers enjoy fun sports meet in terraced fields in Chongyi, E China's Jiangxi

Villagers enjoy fun sports meet in terraced fields in Chongyi, E China's Jiangxi Artisan makes intangible cultural heritage part of modern life in Xining, NW China's Qinghai

Artisan makes intangible cultural heritage part of modern life in Xining, NW China's Qinghai

Copyright © 2025 People's Daily Online. All Rights Reserved.