Migrant workers build a train station. Photo:CFP

When her husband didn't come home on the night of January 12, He Huining called him up. She was told that he was still waiting for his boss to come back to the office so he could get the wages he was owed.

The next morning, she was told to go to their local Shaanxi Province county hospital. Her husband had drunk pesticide and was in intensive care.

Her husband Zheng Xiyun, 54, has been a laborer for a construction company since 2013. The company still owes him and dozens of his colleagues over 500,000 yuan ($73,166.8) in back wages. He had been pressing his boss for the money for weeks, according to a local newspaper.

"I don't care about the money, I just want him back," He told a local newspaper on January 15.

Such incidents occur all over the country, especially before Spring Festival, when millions of migrant workers bring their savings back home. Disputes often end with violent clashes and protests. The authorities sometimes step in to help mediate the disputes and force the companies to pay up, but bureaucracy and political pressure to maintain stability often undermines any role they could play. In the face of the country's slowing economy, there are no signs of such incidents decreasing any time soon.

Tightening belts

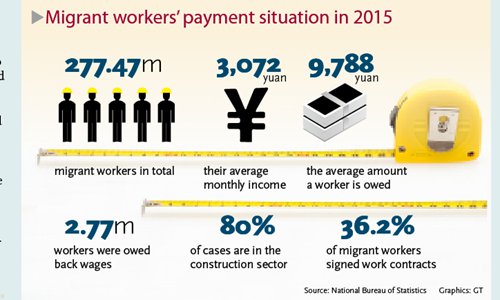

There were over 277 million migrant workers in China by the end of 2015 with an average monthly income of around 3,000 yuan. According to a National Bureau of Statistics report released in April 2016, about 1 percent of migrant workers were owed back wages, 0.2 percentage points higher than the year before.

In 2015, migrant workers were owed on average 9,788 yuan, or more than three months' average wages, according to the bureau. Most of the workers who were owed back pay were in the construction sector. The report also said that those who work in central and western parts of China were more likely to be owed back wages than those who work in China's more developed areas in the eastern parts of the country.

Protests in general have been on the rise in China in recent years as workers become more aware of their rights and assertive in demanding they be respected.

In 2015, the number of strikes and worker protests in China hit a record annual high of 2,774 incidents, doubling the number recorded in 2014, according to the China Labor Bulletin, a Hong Kong-based labor watchdog.

In the first half of 2016, this number has continued to rise, jumping 20 percent compared to the same period in the previous year.

Many factories, especially in prosperous eastern coastal areas and Guangdong Province, have had to shut down or downsize as China's economy slows, exports slide due to weak global demand and firms move their factories to Southeast Asia for cheaper labor. Chinese manual workers often find themselves without basic social security and are sometimes abandoned by their bosses overnight.

Aside from the traditional construction, manufacturing and processing sectors, the payment problem has been prevalent in new online sectors.

The People's Daily earlier this month quoted an unnamed official at the Zhejiang Province human resources and social security department as saying that "there's still a lot of pressure to ensure migrant workers get paid.

The human resources official also told the People's Daily that due to problems such as unstable business models and aggressive expansion, instances of wage arrears are common in the e-commerce, delivery, lifestyle service and transportation sectors that use the Internet.

Battling bosses

Getting bosses to pay up can be an exhausting, even dangerous, task. Lin Qiao, who was in charge of a construction project for a real estate company in Guizhou Province, went to the company's office on November 25, 2016 with nearly 100 construction workers to demand the wages they were owed. Lin and others were beaten by more than 20 men wielding knives and sticks, reported the Chengdu Business Daily.

Seven people were injured including four who were hospitalized. Lin suffered a 20-centimeter cut to his left thigh. Lin said the nerves on his left leg were severed and he has lost all feeling in the appendage, reported the newspaper. The company still owes the workers about 5 million yuan in total.

After they were beaten, the workers reported the incident to the local government and police started to investigate. Other government departments also tried to arrange for negotiations and urge the developer to settle the debt, the newspaper reported.

The judicial system and labor arbitration departments can sometimes play an important role in helping workers. Henan Province courts have made cases of arrears a focus and from 2010 to 2016, they helped 100,000 migrant workers get a total of 2.7 billion yuan in back pay, according to a People's Daily report in April 2016.

Chen Meixin is part of a district level labor inspection team in Nanning, Guangxi Province and the busiest time for her every year is right before Spring Festival.

Since November 1997, Chen has helped tens of thousands of migrant workers get back pay, according to the Xinhua News Agency.

"I've had almost no days off in the past few weeks. The migrant workers want to have their money so that they could go back home for the new year, and we have to help them get the money as soon as possible," said Chen.

"Simplistic" methods

But mostly the authorities are suspicious of the workers and their priorities lie elsewhere. Local courts are evaluated on the number of cases they close each year and in order to hit their quota, some courts simply drop cases involving arrears. Local authorities are also sometimes more concerned with keeping protesters off the streets than actually helping them.

For instance, a district level police bureau in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province issued a warning for employees on its official website on December 29, 2016 of "extreme behavior caused by back pay disputes at the end of the year." The article warned that "incidents of labor-capital disputes are expected to continue to occur at high frequency and the methods are getting more radical."

The authorities seem to place at least part of the blame on the workers.

The warning on the police station website warns of the possibility that workers may get extremely emotional quite easily and even resort to theft, looting and vengeance. The warning says that these "not well-educated" people resort to "simplistic" means.

While workers are more aware of their rights than before, they don't have a thorough understanding of the law and policies, and they are easily influenced by bad examples on TV and the Internet, the police warning says. "[They] think that in order to solve the problems, they have to resort to radical, extreme means so as to get more influence and attention, such as jumping off buildings, blocking roads, or gathering as a crowd to petition," it says.

But for workers, these extreme methods can seem like their only hope. Many newspaper headlines over the years have described migrant workers who have been trying to get back wages for over a decade. Some of them ended up on construction industry blacklists for being "too active" in defending their rights. And many have grown disillusioned with legal means, which can drag on for years and have no guarantee of success.

In December 2016, about 20 people climbed the gate of the Wanda theme park in Nanning, threatening to jump unless their boss paid them, local television reported. The boss reportedly agreed to settle the dispute only after the local government and labor arbitration department got involved.

Zheng, the laborer who drank pesticide, has since regained consciousness. The authorities have intervened in his case and urged the company to pay him as soon as possible.

At 8 pm on January 16, three days after Zheng drank pesticide, it was reported that the company has told workers to come collect their money.

Fire brigade in Shanghai holds group wedding

Fire brigade in Shanghai holds group wedding Tourists enjoy ice sculptures in Datan Town, north China

Tourists enjoy ice sculptures in Datan Town, north China Sunset scenery of Dayan Pagoda in Xi'an

Sunset scenery of Dayan Pagoda in Xi'an Tourists have fun at scenic spot in Nanlong Town, NW China

Tourists have fun at scenic spot in Nanlong Town, NW China Harbin attracts tourists by making best use of ice in winter

Harbin attracts tourists by making best use of ice in winter In pics: FIS Alpine Ski Women's World Cup Slalom

In pics: FIS Alpine Ski Women's World Cup Slalom Black-necked cranes rest at reservoir in Lhunzhub County, Lhasa

Black-necked cranes rest at reservoir in Lhunzhub County, Lhasa China's FAST telescope will be available to foreign scientists in April

China's FAST telescope will be available to foreign scientists in April "She power" plays indispensable role in poverty alleviation

"She power" plays indispensable role in poverty alleviation Top 10 world news events of People's Daily in 2020

Top 10 world news events of People's Daily in 2020 Top 10 China news events of People's Daily in 2020

Top 10 China news events of People's Daily in 2020 Top 10 media buzzwords of 2020

Top 10 media buzzwords of 2020 Year-ender:10 major tourism stories of 2020

Year-ender:10 major tourism stories of 2020 No interference in Venezuelan issues

No interference in Venezuelan issues

Biz prepares for trade spat

Biz prepares for trade spat

Broadcasting Continent

Broadcasting Continent Australia wins Chinese CEOs as US loses

Australia wins Chinese CEOs as US loses