Michael O’Sullivan: Education reflects the culture it is based on

As a pioneer in international education, Michael O'Sullivan has always been at the forefront of the field. Over the past 40 years, he has worked in different areas of education both in the UK and China. At each stage of his career, he has been involved in the most popular and significant field of international education at that time. He has made outstanding contributions to promoting exchanges and collaboration between Chinese and British education.

O’Sullivan is proficient in Chinese and has worked as Director of the British Council in China and as Director of the Cambridge Trust, where he provided financial support to international students at University of Cambridge. He then became Chief Executive of Cambridge International Examinations. Since retiring four years ago, he has worked as an education consultant, and a great deal of the work he does is connected to China.

In his interview with People's Daily Online, O’Sullivan shared with us his views on the differences between Chinese and English education and his insights into the future of international cooperation in education.

Michael O’Sullivan

Opening new doors

People’s Daily Online: When did you start to learn Chinese, and when was the first time you engaged in something related to China?

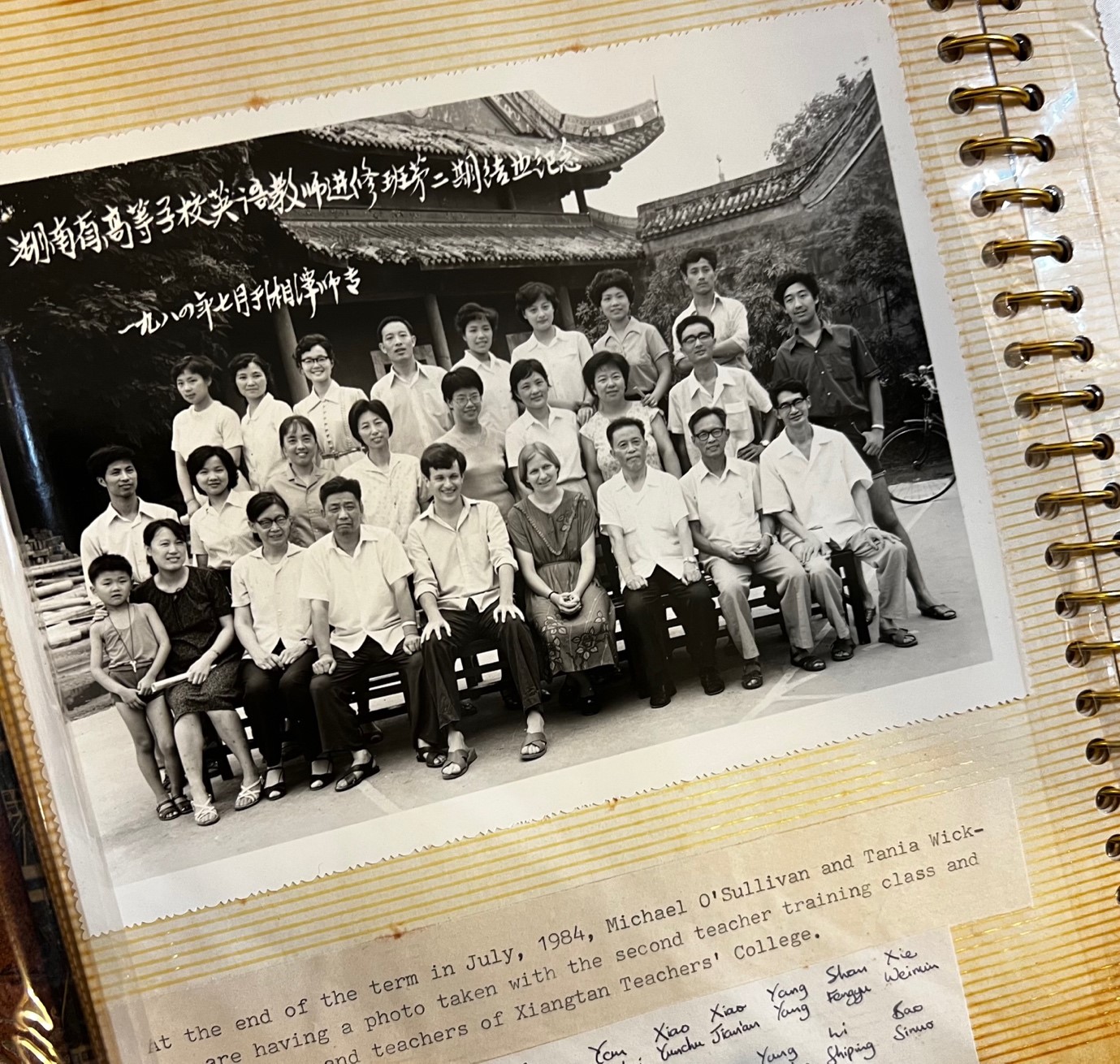

Michael O’Sullivan: When I was a very young child, I used to collect postage stamps. I remember the postage stamps of China at that time that had pictures of very large numbers of people wearing green and blue suits. I suppose they were China as it looked at that time, and it just seemed to be completely different to anything I was familiar with in the UK or in Europe. So I suppose that which is completely different from our own experience is always fascinating. Certainly to me, it’s always been worth exploring that which you don’t know. I came to China for the first time in 1982 as an English teacher in Hunan Province, and my first Chinese lesson was three weeks before I left the UK for China.

People’s Daily Online: Why did you decide to go to China at a time when very few foreigners had the opportunity or any interest in going there?

Michael O’Sullivan: There were very few foreigners in China in the early 1980s. But of course, China had already embarked on a new era of reform and opening so it was possible to go to China, but as of that time very few people had done it. I felt a great curiosity to go to China at that time, and thought the opportunity to learn the Chinese language would be very worthwhile. After three months, I began to feel that I understood people better, and that essentially there was great warmth and friendship in both directions, despite the huge cultural differences and different experiences at the time. I stayed there for two years. That was my contract.

People’s Daily Online: What kind of work did you do in the UK or China after your two-year teaching stint in China?

Michael O’Sullivan: It wasn’t very long after I returned from China in 1984 until I went there again. I joined the British Council the following year in 1985, and in 1987, I was posted to Beijing as Second Secretary in the Cultural Section of the British Embassy, working for the British Council. I stayed there for nearly four years at that time, so I spent quite a lot of the 1980s living in China – more than I spent living in the UK.

But in the year 2000, I moved to China to Beijing with my family as the Director of the British Council in China, and then we lived in Beijing for eight years. After leaving the British Council, I remained in Beijing. I was Secretary General of the European Chamber of Commerce.

But then I returned to the UK and moved here to Cambridge in 2008, and in Cambridge first I was Director of the Cambridge Trust, where I was providing financial support to international students at Cambridge University. Then I was Chief Executive of Cambridge International Examinations. Both those jobs involved many visits to China, because we cooperated a lot with partners and with schools in China. Since I retired from CEO at Cambridge International Examinations four years ago, I’ve worked as an education consultant and a lot of the work I do is with China, so I am a frequent visitor these days to China.

Behind the continuous enthusiasm for studying abroad

People’s Daily Online: You've been working in education for a very long time. Can you talk about the trend or learning boom in international education in the 1980s or 1990s?

Michael O’Sullivan: Yes, I suppose at different times over the last 40 years, I’ve worked in different areas of education between the UK and China, and at each stage, what I’ve been doing has been the most popular, busiest aspect of collaboration at that time in education.

In the early 1980s, it seemed all China wanted to learn English. There was such enthusiasm that complete strangers would walk up to me in the streets, or even in the countryside, and start practicing English because they spotted a foreign face and were so eager to learn. That was the great time for learning English.

Then in the late 80s, I was very much involved in helping huge numbers of young Chinese people and also experienced Chinese academics come to the UK to study at our universities here, and that was the big trend of that time. They came here in very large numbers to do PhDs in British universities or as visiting scholars. Many of them went on to achieve great things in China.

I suppose with the changing nature of the educational relationship between China and the West over the last 40 years, also my work opportunities have changed.

People’s Daily Online: Chinese students make up the largest cohort of international students in the United Kingdom. Why are Chinese students so keen on studying overseas, in particular in the UK?

Michael O’Sullivan: I think that Chinese people are by and large very curious about the outside world, and very curious about Western countries and the UK. In contrast, I think genuine interest in China in the UK and the West exists, but it’s really only observable in a minority of people. I think a lot of people are not that curious about China; not negative, but they don’t spend a lot of time trying to find out more. But in China, I think curiosity about the outside world is a very general characteristic of people, and I’ve always found that interesting, that I get asked so much about how things really are in the UK and in Western countries, why things are like that.

So I think a lot of the interest in learning English, and in some cases coming to the West for education, has been driven by a desire to understand that which is outside the direct experience of Chinese people in their own country. I think that’s been a feature of Chinese civilisation over a very long period, and actually is quite the opposite to what people sometimes think.

People sometimes think China is a relatively closed society looking in on itself, and they will quote examples from Chinese history to try to prove this point. But I think that’s just looking selectively for evidence to prove a point of view which I actually don’t agree with. My own experience of China and my reading of much of Chinese history is there’s always been, as there is now, a huge curiosity to learn from outside and to study the rest of the world, and evaluate it with care.

Chinese and British education should learn from each other

People’s Daily Online: In your opinion, what is the main difference between British and Chinese education?

Michael O’Sullivan: I think in China generally, there is a huge effort to succeed in education, so families almost always give great importance to their children’s educational success.

In China, there are good sides to this and there are also challenges. So children in China sometimes feel, I think, too pressured to gain grades in exams. But on the other hand, this huge support that families give to their children’s education does set a good example, and does allow people to succeed and improve their lives.

In the UK, I would say we are on the whole more relaxed about our children’s education. We are more ready to say, “not every child is suitable to go to Oxford or Cambridge.” I think they could be more discerning about the differences between children and realise that the same route isn’t right for everybody.

People’s Daily Online: In your view, what are the major advantages and disadvantages of each education system? What can Chinese and British educators learn from each other's education systems?

Michael O’Sullivan: I think one of the greatest things that Chinese educators can learn from British education – and many of them study this – is that giving children more choice about which subjects they study at various ages of their education can improve children’s motivation and the happiness they get from learning, and can also help to produce students who are experts in different fields. So choice is a powerful aspect of British education which is worthy of study, and is indeed studied by Chinese educators.

On the other hand, when British educators look at China, they should study carefully the value of setting high expectations for every child. High expectations aren’t always met, but if expectations are high, I do think it leads often to greater achievement, greater effort, and greater self-confidence, greater ambition. In the UK, I sometimes think we would do well to reflect on how that’s done in China

People’s Daily Online: Many scholars, education administrators and investors in China are discussing how to improve creativity and original scientific research in China through education. Do you think there is a creativity problem in China?

Michael O’Sullivan: I’m not convinced there’s a great deficit of creativity in China. I think this is probably an out-of-date perception.

If you look around China and look at the energy and success of many Chinese companies and also some non-commercial activities, you would see a lot of creativity. So in the commercial fields, you see Chinese companies that are at the leading edge of many technologies, and it seems to me that it would be impossible if they weren’t creative and the people who work for them are not creative. If you look at Chinese film over the last 40 years, all of the visual arts in China, you see evidence of great creativity. So why is it that people in China, and people outside of China, sometimes talk about this problem of insufficient creativity?

People’s Daily Online: How can collaboration in education circles play an important role in international relations? Will it lead to more harmony?

Michael O’Sullivan: Education systems are different in every country, and I don’t think any country’s education system is suitable to be transplanted into another country because education reflects the culture in which it is located. So I think we should not ever recommend looking at other education systems as models to adopt verbatim.

However, I think studying other education systems and evaluating them carefully helps us to understand our own education system better, and to spot opportunities and to spot weaknesses and deal with them. Studying other education systems makes you more critically aware of your own education and how to improve it.

Photos

Related Stories

- Artificial intelligence charts course for educational reforms

- Yearender: China strives to improve people's well-being, raise quality of life

- Experts say Pakistan-China collaboration on education, cultural exchange on upward trajectory

- Peter Cavaciuti: Injecting Chinese artistic spirit into foreign soil

- Michael Sheringham: A generational family business, a century-long cultural connection

- Interview: London's Royal Albert Hall hopes to attract more Chinese artists, spectators: CEO

- Alan Macfarlane, social anthropologist at University of Cambridge: Playing a concerto of civilisations

- China hopes Britain will nurture bilateral cooperation: FM spokesperson

- Mark Pollard: An obsession with China that isn’t going away

- Higher standards set to improve vocational schools

Copyright © 2022 People's Daily Online. All Rights Reserved.