|

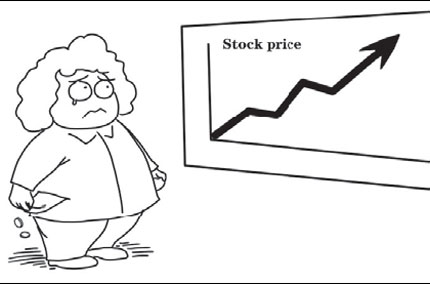

| Illustration by Zhou Tao |

Gold has a timeless allure - especially if you worry about stock market volatility, inflation, a decay of ordinary currency or the collapse of civilization.

Yet not everyone agrees that gold offers the safe haven its promoters describe. After soaring for a dozen years, it has plummeted in 2013.

After all, while gold has some practical uses in electronics and a few manufacturing processes, most of it ends up as jewelry on people's wrists and necks - or rests quietly as stacks of ingots in rooms with thick doors and strong floors.

What is the proper role for gold in an investment portfolio? Why has its price been falling?

"People call it an insurance policy. I call it a very expensive insurance policy," says Wharton finance professor Jeremy Siegel.

"I would never recommend a specific investment in gold," adds Kent Smetters, professor of business economics and public policy at Wharton, who adds that investors have better ways to hedge against inflation - one of gold's presumed benefits.

Spotty record

There is no denying that gold has held value for humans for thousands of years. It is found in the graves of the elite all over the world. The search for it drove much of the exploration of the New World. Treasure hunters risk their lives pursuing chests of it lost at the bottom of the sea.

But its record as a store of wealth is spotty. From early 2001 to late summer 2011, the price of gold soared from just under US$300 an ounce to nearly US$1,900, confirming gold proponents' view that the metal is a terrific investment.

But there have been long periods of disappointment, too. Gold peaked just shy of US$700 an ounce in 1980, then fell and did not again hit that level for 27 years. It started this year at US$1,657, and has fallen about 18 percent to around US$1,355, while the Standard & Poor's 500 Index has gained about 18 percent.

The cause of these ups and downs is always open to debate.

Among the largest consumers of gold are jewelry buyers in India, says Wharton finance professor Franklin Allen. "India has not been doing well, so that may be a factor" driving gold prices down, he notes. "There may also be some selling by central banks and hedge funds that we aren't aware of."

Gold prices are also affected by the ebb and flow of demand for other investments. If stocks look good, some investors will switch from gold to stocks, and falling demand will help drive gold prices down. Gold's fall this year coincides with a fast climb in stock prices. "Gold and silver are suffering because people are moving money to the stock market," Smetters says.

Siegel maintains a long-run chart of real returns for various asset classes - returns adjusted for inflation.

Because of inflation, a dollar acquired in 1802 would have been worth just 5.2 cents at the end of 2011. A dollar put into Treasury bills at the same time would have grown to US$282, or to US$1,632 had it gone into long-term bonds. Held in gold, it would have grown to US$4.50.

True, that's a gain even with inflation taken into account. But the same dollar put into a basket of stocks reflecting the broad market would have grown to an astounding US$706,199.

As an investment, gold has some flaws. Anyone who owns it in significant quantity would be wise to ante up for secure storage, which creates a cost that drags on the return, says Siegel. And, unlike bank savings, bonds or dividend-paying stocks, gold does not provide income. "It's a very volatile asset with no yield," according to Allen.

Nor does gold provide rights to share in corporate profits - a perk enjoyed by any stockholder. Investors who want safety can use government bonds, knowing the government can use its taxing power to make good on its commitments to bond owners. No one stands behind the price of gold.

In a period of hyperinflation, when currency becomes virtually worthless, or a time of great distrust in the economy or banking system, gold may indeed become a safe haven, Siegel notes. "There isn't anything that's clearly better if you're concerned about those sorts of events."

But he adds that people who turn to gold tend to be "overly concerned" about catastrophe. Putting a large portion of one's wealth into gold would therefore mean sitting on the sidelines waiting for an unlikely event while other assets, such as stocks, produced better long-term returns.

Currently, inflation is very low, which eliminates that factor as an immediate reason to hold gold, Smetters points out. Investors who worry deeply about other asset classes can put a small portion of their holdings into gold for peace of mind, so long as they are willing to pay a price in storage costs and weak returns, Siegel says.

Illustration by Zhou Tao

Buy the mine instead

Most experts caution against investing in jewelry and collectable coins, because it's hard to assess the artistic or collectable value that comes on top of the value of the raw gold.

Professional investors trade gold on the futures market - but this is very complex, and futures are generally used for short-term bets rather than long-term investments.

As a compromise, investors can buy stocks in gold mining companies, says Allen. These stocks give shareholders the right to share in cash flows, and they tend to benefit when gold rises, though investors must also assess the quality of management, the firm's competiveness in the market and any other factors involved in a stock purchase.

People cool off in water from orange-coded alert of heat in Chongqing

People cool off in water from orange-coded alert of heat in Chongqing

![]()