|

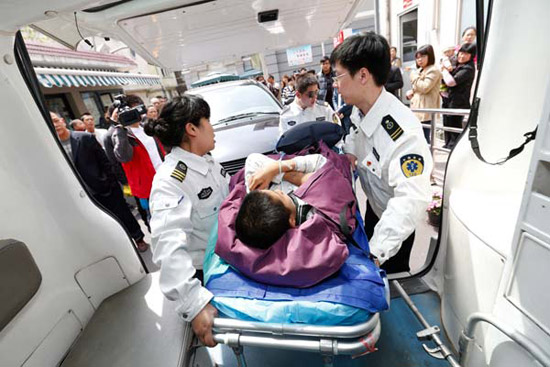

| Staff at Shanghai Medical Emergency Center transfer a child, who arrived at the city's South Railway Station from Yunnan province, to Children's Hospital of Shanghai. PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY |

Low salary, high stress and lack of staff plague emergency crews

For Li Minghua, the sound of a phone ringing sends his heart racing and causes him to break into a sweat.

"That's why I don't have a fixed landline at home," he said, joking that it is a side effect of years working as an ambulance medic in Shanghai.

The 35-year-old doctor has been a first responder for eight years and now works as a trainer for the Shanghai Medical Emergency Center, which has more than 110 ambulances covering the large downtown area.

Li is among only a handful of doctors who have stuck with the job for so long. Most leave after a year due to the low salary and high-stress environment.

According to Shanghai Health and Family Planning Commission, the city has about 2,275 ambulance workers. Yet most are drivers and nurses, less than 30 percent are trained doctors and the number has been steadily dwindling.

Last year, for example, the emergency center recruited 31 doctors, while at the same time 55 quit.

Shanghai has more than 240 ambulances, which are on day and night shift by turns, Li said, estimating that on an ordinary day they can be dispatched 1,000 times.

"It's higher at peak times," he said. "An ambulance doctor will be sent out at least 12 times during a 12-hour shift. The work leaves us totally stressed out, and many develop back or knee injuries from lifting and carrying patients.

"And almost every doctor has faced abuse from patients or their relatives. Some have even been beaten up," he said.

The decrease in resources goes some way to explaining why complaints about the city's emergency response service have been so common in recent years. The latest to make headlines came in mid-April after an ambulance failed to show up to help a British boy with head injuries, despite two calls being made to the 120 hotline.

The 3-year-old was hurt when a large, wooden folding screen fell onto him as he played at Kervan Orient Express. According to Sun Ying, owner of the Turkish restaurant in the central business district, a 120 call center worker said all ambulances were busy and suggested she call a taxi to take him to hospital.

The child's parents opted to take him by cab to Shuguang Hospital, the nearest medical clinic. However, they arrived to discover it did not have an emergency room and had to then travel to a second hospital, where the boy was pronounced dead.

"I don't understand," Sun said in late April, still clearly traumatized by the incident. "An ambulance never came, even after we'd sent the boy's body to the funeral home."

![]()