|

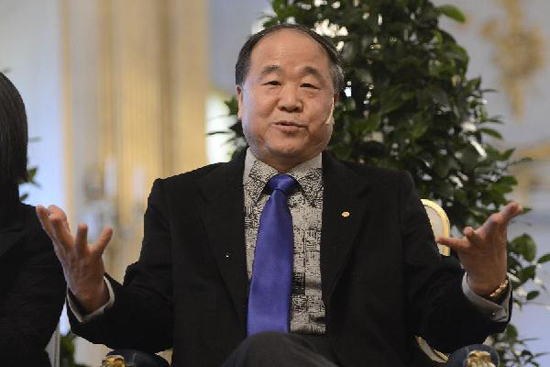

| Mo Yan, this year's winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, attends a press conference in Stockholm, capital of Sweden, on Dec. 6, 2012. (Xinhua/Wu Wei) |

Mo Yan has been known for years, but his books were far from best-sellers in China, or in Sweden - until he won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Now he's hot, but what does this mean for serious Chinese writing? Yao Minji explores his impact.

Rread more: Designer unveils Mo Yan's dressing code

Mo Yan, the first Chinese national to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, today (early tomorrow morning, Beijing time) receives the award in Stockholm, Sweden, where his contributions to Chinese and world literature will be recognized.

After the announcement that he had won the prize, "Mo mania" swept the nation and his books were sold out immediately. His hometown launched a tourism campaign featuring Mo's humble family home and his books, which are mostly set in poor, rural Shandong Province where Mo was born in 1955.

Prices of Chinese publishing and related stocks surged on China's exchanges in anticipation of high book sales. Even what Mo will wear when accepting the prize has become a hot topic. Some Chinese want him to wear a traditional Hanfu gown, but Mo, whose real name is Guan Moye, is more likely to wear a suit and tie.

Read more: No gold medal in literature

Mo Yan, whose pen name means "don't speak," has published 11 novels, 20 novelettes and many short stories and plays. His Chinese publisher released a collection of three stage scripts after he won the Nobel, and his latest published novel was "Frog," one discussing the one-child policy in China.

It is not available in English yet, but his earlier novels "Life and Death are Wearing Me Out," "Red Sorghum Clan" (1987), "The Garlic Ballad" (1988), "Pow!" (2003), "The Republic of Wine" (1992), "Big Breasts and Wide Hips" (1996) and "Sandalwood Death" (2004) have all been translated in English by Howard Goldblatt.

Mo himself recommends "Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out" to foreign readers. Speaking as he arrived in Stockholm, he said in answer to a question, "(It is) a story not only featuring imagination and fairy-tales, but also the history of modern China."

"It (Mo's winning) is a significant event and sort of a landmark showing that Chinese literature has been accepted and acknowledged by the world. So the mania is understandable. But now it is time to calm down and look at literature itself. It's time to look at the impact of the event on the future of Chinese contemporary literature," says Lei Da, a well-established Chinese literature critic based in Beijing.

"Mo Yan was never the top writer in China, he was one of the top writers who were nurtured from contemporary Chinese literature in the past 30 years, during which they learned from the west and merged such western influence with their Chinese-rooted stories and styles." Lei was one of the first critics to review Mo's works.

Mo's works became well known because of the movie "Red Sorghum" (1987) by director Zhang Yimou, adapted from his 1986 novel of the same name.

"This (Mo's winning) is significant since not the best contemporary Chinese writer got the prize," Dr Wolfgang Kubin, a famous German translator, tells Shanghai Daily in a recent e-mail interview.

Cumquat market in S China's Guangxi

Cumquat market in S China's Guangxi

![]()