|

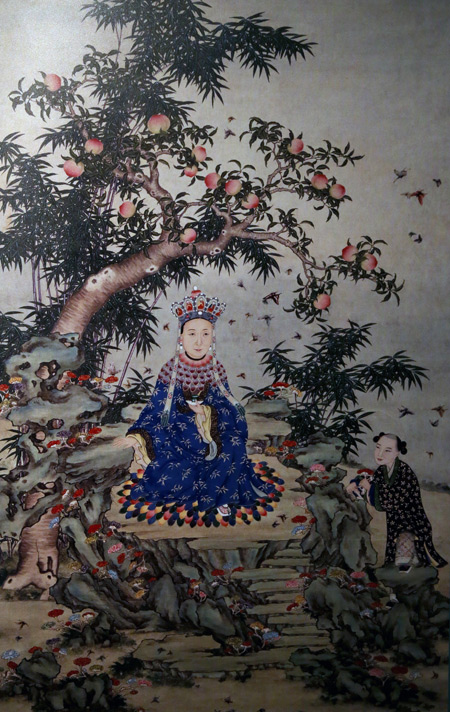

| A portrait of Ci Xi, dressed up as Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy. (China Daily/Jiang Dong) |

The collection starts not with Ci Xi, but with her son, the Emperor Tongzhi, whose birth in 1856 first placed the 22-year-old royal concubine on the competitive path to becoming the country's most powerful person.

A collection of bowls, spoons and teacups launches the exhibition, specially commissioned for the grand wedding of the young emperor in 1872. True to the occasion, coral red and imperial yellow are extensively used, while auspicious icons of bats and magpies adorn the collection. To the Chinese, the homophonic representations of these creatures are supposed to usher in harmony and good fortune.

Another recurring motif is the gourd vine-and-butterfly, symbolizing productivity. With the line of succession already being threatened, this was a priority with the royal family. Unfortunately, historic evidence showed that the wish was not granted.

Tongzhi was the only male heir from his father, Emperor Xianfeng, and he himself died young at the tender age of 19, and left no children. The same fate befell his cousin and successor, Emperor Guangxu, Ci Xi's nephew by her twin sister.

After this first interlude, the rest of the exhibition is devoted to the Empress Dowager, fuelled mainly by her birthday celebrations, which necessitated the production of large amounts of porcelain, at a huge expense and often taxing a cash-strapped treasury.

On these occasions, Ci Xi gave way to her feminine impulses with abandon, opting for the riotous and previously rarely used deep purple and turquoise green while replacing the conventional landscape-and-character motifs with an exuberance of flowers.

Man's 20-year habit leads to kidney stone

Man's 20-year habit leads to kidney stone

![]()