|

| (Photo from China.org.cn) |

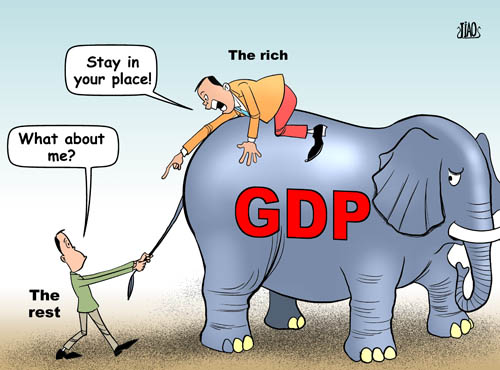

China's Gini coefficient, an index reflecting the wealth gap, stood at 0.462 in 2015, the latest data released by the National Bureau of Statistics showed. That number is down from the year before, as it has been decreasing for the past seven years. Analysts say that the consecutive drops indicate more equality in China’s income distribution and show the central government’s achievements in distribution reform.

Once again outpacing GDP growth, per capita disposable income reached 21,966 yuan ($3,349) in 2015, up 7.4 percent from 2014 in real terms. The average monthly income of rural migrant workers increased by 7.2 percent from the year before to 3,072 yuan last year.

Despite slowed economic growth, and thanks to better employment and the rise of labor costs, disposable income has seen an overall increase, experts said.

China’s Gini coefficient also fell to 0.469 in 2014 after its peak of 0.491 in 2008. The drop, according to experts, can be attributed to measures taken by the Chinese government in the past five years to reform the income distribution system.

Such measures include raising individual income tax thresholds, reforming the pension system, raising the minimum wage and a variety of others.

Even so, the index still exceeds 0.4, which is generally regarded as the international warning level for dangerous levels of inequality. China still faces a noticeable wealth gap.

According to a study conducted by the Southwest University of Finance and Economics, real estate accounts for 69.2 percent of China’s average household property, revealing a lack of mobility.

The 2015 China Family Development Report, released by the National Health and Family Planning Commission, showed that the income of the richest 20 percent of families is 19 times that of the poorest 20 percent.

Institutional factors are the main reason for income inequality, Li Shi, a professor at Beijing Normal University, pointed out. The household registration system has caused a dual-track in social welfare composed of urban residents and rural migrant workers, Li elaborated.

Under China’s economic “new normal,” which puts more emphasis on restructuring the economy, many over-capacity companies are at risk of being shut down. This could lead to unemployment or a drop in salary for workers, while employees in emerging industries are able to earn more money in a shorter time, said Su Hainan, Deputy Director of the China Association for Labor Studies.

Narrowing the income gap remains a priority during China’s 13th Five-Year Plan period from 2016 to 2020, noted Yin Weimin, head of the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security.

Liu Junsheng, a senior researcher with the Ministry, believes the key lies in increasing minimum wage and expanding the pool of people with medium incomes. “The ultimate goal is to form an olive-shaped income distribution pattern,” explained Liu.

Su suggests reforms in salary regulation of listed companies and governmental organizations.

A foreign girl explains what China should be proud of

A foreign girl explains what China should be proud of Chinese navy's air-cushioned landing craft in pictures

Chinese navy's air-cushioned landing craft in pictures Chinese pole dancing master opens class in Tianjin

Chinese pole dancing master opens class in Tianjin PLA holds joint air-ground military drill

PLA holds joint air-ground military drill Charming female soldiers on Xisha Islands

Charming female soldiers on Xisha Islands Beautiful skiers wear shorts in snow

Beautiful skiers wear shorts in snow Getting close to the crew on China's aircraft carrier

Getting close to the crew on China's aircraft carrier Chinese stewardess celebrate test flight at Nansha Islands

Chinese stewardess celebrate test flight at Nansha Islands Pentagonal Mart becomes the largest vacant building in Shanghai

Pentagonal Mart becomes the largest vacant building in Shanghai Top 20 hottest women in the world in 2014

Top 20 hottest women in the world in 2014 Top 10 hardest languages to learn

Top 10 hardest languages to learn 10 Chinese female stars with most beautiful faces

10 Chinese female stars with most beautiful faces China’s Top 10 Unique Bridges, Highways and Roads

China’s Top 10 Unique Bridges, Highways and Roads Virtual reality takes porn ‘to the next level’

Virtual reality takes porn ‘to the next level’ Online spat won’t hinder cross-Straits ties

Online spat won’t hinder cross-Straits ties A look behind the scenes at China’s censorship watchdog

A look behind the scenes at China’s censorship watchdog $93m gay app deal raises questions over future of LGBT services

$93m gay app deal raises questions over future of LGBT servicesDay|Week