|

| A guide walks visitors through the exhibits in Flying Tigers Memorial Museum on Feb. 27, 2014. (Photo/Chinanews.com) |

Since returning home after my recent trip to China in March, I have reflected on my experiences about the land and the people that my grandfather, General Chennault loved so much. It was a great honor to be invited to the opening of the Flying Tiger Heritage Park in Guilin. The Chinese people have become my extended family and it is with a grateful spirit that I join with my extended family to tell the story of my grandfather and the Flying Tigers. While many may know of the heroics of the Flying Tigers, they may not know the circumstances that led my grandfather to China, why he stayed, or the difficulties he faced.

Chennault went to China in 1937 by invitation of Soon Mei-Ling. He accepted her invitation because, as he wrote to his brother Bill, the job “may amount to very little except a good paying position, but it may amount to a great deal…It is even possible that my ‘feeble’ efforts may influence history. I couldn’t possibly pass up this opportunity for, after all, very few boys from Gilbert, La., will ever have the slightest chance to influence the history of the future years.”

The bombing of the Marco Polo Bridge (or Lugou Bridge, simplified Chinese: 卢沟桥) near Peking convinced Chennault that he needed to stay. In Way of a Fighter, Chennault wrote, “I was convinced that the Sino-Japanese War would be the prelude to a great Pacific War involving the United States.” Chennault saw the devastation caused by Japanese bombers. He did not stay because he wanted to help a foreign country; he stayed because he wanted to help his fellow man. He never, after all, ran from a fight.

Their challenge was great and Chennault and his pilots seemed to face insurmountable odds. There were never more than 50 planes ready for combat at any one time. Parts were always in short supply and to keep the Flying Tigers in the air, mechanics had to, at times, patch bullet holes with chewing gum and tape. Chennault praised the ground crews in Way of a Fighter,”it was the speed with which the ground crews repaired, refueled, and rearmed the P-40’s that kept the AVG from being floored by the Japanese one-two punches. The ground crews displayed ingenuity and energy in repairing battle-damaged P-40’s that I have seldom seen equaled and never excelled.”

Time and time again, the pilots not only succeeded, they triumphed but the number of Japanese aircraft the AVG silenced would have not been possible if it weren’t for the tactical innovations Chennault developed. Chennault taught his pilots to fight in pairs; to use speed and diving power to make a pass, shoot and break away. With the success of the early warning net Chennault had created, the AVG destroyed close to 300 enemy aircraft while only losing 12 of their own. In combat they were outnumbered at least ten to one. Surviving the odds, the Tigers were never beaten in battle. Later, under Chennault’s command, the 14th Air Force destroyed more than 2,600 enemy aircraft, sunk or damaged 2,230,000 tons of enemy merchant vessels and 45 naval ships and killed more than 66, 700 enemy troops – with the smallest and most remote air force in World War II.

Chennault’s love, respect and admiration for the Chinese people was not limited to political affiliation or region. He did not fight for fame or career advancement. He fought because he believed in the value of every life. As Director of the Chennault Aviation and Military Museum, I work to continue my grandfather’s mission and to strengthen U.S.-China relations by building on the goodwill left by Chennault and the Flying Tigers.

The Museum focuses on building mutual understanding between people through informational, educational and cultural programs. We have enlisted the support of experienced educators who have created programs to work with individuals, multinational companies and organizations that would like to do business with China and to gain a better understanding of the language and culture of both the U.S. and China.

When the war ended, we left each other as friends, saddened to see the other leave but thankful for the friendship that was formed and the peace that was established. Now, almost 70 years later, I know that our work is not finished. While old enemies have been defeated, challenges still remain and if there is to be peace in the 21st century, China and the United States must become partners.

In 1949, my grandfather ended his memoir, Way of the Fighter with this, “It is my fondest hope that the sign of the Flying Tiger will remain aloft just as long as it is needed and that it will always be remembered on both shores of the Pacific as the symbol of two great peoples working toward a common goal in war and peace.” My grandfather’s words hold as much importance now in 2015 as they did in 1949.

I look forward to carrying on the work that General Chennault began and remember the friendship that our countries created by defeating the Japanese. In September 2015, the Chennault Aviation & Military Museum will hold a grand opening event to formally dedicate the exhibit, Way of a Fighter which gives Chennault’s first person point of view and offers a deeper connection to those who fought and died, both civilian and military and explores the Pacific Theatre as few know. The event will also remember the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II and the Allie’s victory.

The author is Director of the Chennault Aviation and Military Museum, granddaughter of General Chennault

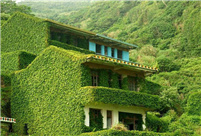

Abandoned village swallowed by nature

Abandoned village swallowed by nature Graduation: the time to show beauty in strength

Graduation: the time to show beauty in strength School life of students in a military college

School life of students in a military college Top 16 Chinese cities with the best air quality in 2014

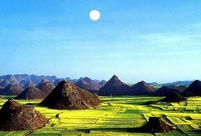

Top 16 Chinese cities with the best air quality in 2014 Mysterious “sky road” in Mount Dawagengzha

Mysterious “sky road” in Mount Dawagengzha Students with Weifang Medical University take graduation photos

Students with Weifang Medical University take graduation photos PLA soldiers conduct 10-kilometer long range raid

PLA soldiers conduct 10-kilometer long range raid Stars who aced national exams

Stars who aced national exams

PLA helicopters travel 2,000 kilometers in maneuver drill

PLA helicopters travel 2,000 kilometers in maneuver drill Investment slows to 15-year low

Investment slows to 15-year low China, Myanmar focus on win-win ties

China, Myanmar focus on win-win ties Dangerous stigma

Dangerous stigma Smashing drug addiction

Smashing drug addictionDay|Week