'Jin' named the word of the year by cross-strait netizens

'Jin' named the word of the year by cross-strait netizens Chinese scientific expedition goes to build new Antarctica station

Chinese scientific expedition goes to build new Antarctica station

Chinese naval escort fleet conducts replenishment in Indian Ocean

Chinese naval escort fleet conducts replenishment in Indian Ocean 17th joint patrol of Mekong River to start

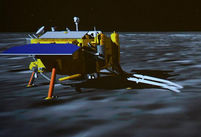

17th joint patrol of Mekong River to start China's moon rover, lander photograph each other

China's moon rover, lander photograph each other Teaming up against polluters

Teaming up against polluters

BEIJING, Jan. 4 -- A century ago, children outnumbered the elderly by as much as 10 to one in most European countries. Today, there are as many people over the age of 65 as there are under the age of 16. In the United Kingdom, roughly one in six people is 65 or older, compared to one in eight Americans, and one in four Japanese.

This shift has been powered by declining birth and infant-mortality rates in the first half of the 20th century, together with rising life expectancy in recent decades. Whatever the causes, many are concerned that, in the coming decades, rapidly aging populations will increasingly strain health, welfare, and social-insurance systems, putting unsustainable pressure on public budgets.

But, while such fears are not entirely unfounded, discussions about population aging tend to exaggerate the trend’s scale, speed, and impact, owing to a fundamental misperception about how populations grow older. Unlike people, populations do not follow the life cycle of birth, aging, and death. And, while a population’s age distribution may change, age becomes an unreliable way to measure a population’s productivity as lifespans increase.

Age has two components: the number of years a person has lived (which is easy to measure for individuals and populations) and the number of years a person has left to live (which is unknown for individuals, but possible to predict for populations). As mortality declines, remaining life expectancy (RLE) increases for people of all ages. This distinction is crucial, because many behaviors and attitudes (including those that are health-related) may be linked more strongly to remaining life expectancy than to age.

The standard indicator of population aging is the old-age dependency ratio (OADR), which divides the number of people who have reached the state pension age by the number of working-age adults. But this approach fails to distinguish between being of working age and actually working, while classifying all people above the statutory pension age as dependents.

In fact, social and economic shifts have broken the link between age and dependency. Young people spend an increasing number of years in education, while many older workers retire early, implying that they have sufficient personal savings. In the UK, the 9.5 million working-age dependents (those who are not in paid employment) outnumber those who are above the state pension age and do not work.

Moreover, the old-age dependency ratio disregards how, over time, rising life expectancies effectively make people of the same chronological age younger. In 1950, a 65-year-old British woman had an average life expectancy of 14 years; today, she can expect to live another 21 years (the figures are 12 and 18 years, respectively, for men).

Different trends

Many other countries, especially in the developed world, have experienced similar shifts, with life expectancy having increased the most in Japan.

Meanwhile, some Eastern European countries still lag behind, with no increase having been observed in Russia since 1950.

A better measure of population aging’s impact is the real elderly dependency ratio (REDR), which divides the total number of people with a remaining life expectance of 15 years or less by the number of people actually in employment, regardless of their age. This measure accounts for the real impact of changes in mortality, by allowing the old age boundary to shift as advances in health prolong people’s productive lifespans.

In recent decades, as the old age dependency ratio has risen in advanced countries, the real elderly dependency ratio has declined. It has, however, stabilized, and is likely to increase gradually over the next couple of decades. In Germany and Italy, the real elderly dependency ratio has been almost flat for two decades, owing to slower employment growth and lower birth rates than elsewhere in the developed world.

Immigration has played an important role in depressing many countries’ real elderly dependency ratio by raising employment rates. Increased labor-force participation among women has also helped to lower real elderly dependency ratios.

Of course, failure to support these trends has the opposite effect. Japan where opposition to immigration and failure to embrace gender equality have led to a rapidly rising real elderly dependency ratio is a case in point.

Russia, too, has experienced a substantial increase in its real elderly dependency ratio, owing to post-communist economic dislocation. But the rest of the major emerging economies still have relatively low real elderly dependency ratios.

In short, the real elderly dependency ratio tells a very different story from the old age dependency ratio, with at least three important policy implications. First, population aging is no excuse for trimming the welfare state or treating pension arrangements as unsustainable.

After all, the phenomenon has been underway for more than a century, and, in some respects, its social and economic impact has been declining in recent decades.

Moreover, the real elderly dependency ratio underscores that rising demand for health care and social services is not a function of having a larger share of people above a specific age.

Factors like progress in medical knowledge and technology, and the increasing complexity of age-related conditions, are far more relevant.

Implications

In fact, while age-specific disability rates seem to be falling, recent generations have a worse risk-factor profile than older ones, owing to trends such as rising obesity rates. The capacity of health-care systems to cope with increasing longevity will therefore depend on the changing relationship between morbidity and remaining life expectancy.

The third implication concerns higher education.

Elderly people with university degrees (a small minority of their generation) enjoy a substantial longevity advantage. If the life-enhancing effect of higher education persists, population aging can be expected to accelerate further, as the younger, larger, and more highly educated generations grow older.

Preparing for and coping with changing demographics requires a more nuanced understanding of what population aging really means. For that, the right indicator — the real elderly dependency ratio — is essential.

John MacInnes is professor of sociology and Jeroen Spijker is a senior research fellow at the School of Social and Political Science, University of Edinburgh. Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2013. www.project-syndicate.org

Chinese Consulate General in S.F. burned for arson attack

Chinese Consulate General in S.F. burned for arson attack Roar of J-15 fighter is melody for operator on the Liaoning

Roar of J-15 fighter is melody for operator on the Liaoning A 90-year-old forester's four decades

A 90-year-old forester's four decades Most touching moments in 2013

Most touching moments in 2013 2013: Joys and sorrows of world politicians

2013: Joys and sorrows of world politicians Missile destroyer Zhengzhou commissioned to Chinese navy

Missile destroyer Zhengzhou commissioned to Chinese navy China is technically ready to explore Mars

China is technically ready to explore Mars Photo story: Life changed by mobile technology

Photo story: Life changed by mobile technology Bullet train attendants' Christmas Eve

Bullet train attendants' Christmas Eve Most touching moments in 2013

Most touching moments in 2013 Chinese helicopter saves 52 in Antarctica

Chinese helicopter saves 52 in Antarctica PLA self-propelled guns firing in drill

PLA self-propelled guns firing in drill Those That Shaped 2013

Those That Shaped 2013 Yearender: Animals' life in 2013

Yearender: Animals' life in 2013 Hello 2014 - Chinese greet the New Year

Hello 2014 - Chinese greet the New YearDay|Week|Month