|

| (Photo provided to People's Daily Online) |

Before the reforms began, visitors from outside China were often stunned at the sight of the drab, sexless clothes worn by the Chinese. For men, the tonic dress was the so-called "Mao jacket," a plain, high-collared shirt-like jacket mostly gray, blue or green, so named because it was customarily worn by Mao Zedong and other top leaders. Women often wore loose jackets and trousers to cover up their feminine beauty, for fear of being condemned for living a "corrupt bourgeois way of life." Exactly like what is said in a comic talk popular in the late 1970s and early 1980s, every Chinese woman had once looked like an "iron man" when she showed up in a public place.

Bell-bottoms, dubbed as "trumpet trousers" for being wide legged below the knee, became popular when I was at middle school in the first half of the 1980s. Women bold enough to have their hair permed were often frowned upon by neighbors and colleagues. At my school, boys wearing bell-bottoms and girls with a few curls on their hair were often reprimanded for being bad in behavior.

A teacher named Zhang was reprimanding a boy when I entered her office room one day. The boy's parents were also there. "Look at him," said Zhang, pointing at me. "A good student must be dressed the way he is!" I looked at what I was wearing, somewhat confused – a blue Mao jacket, and a pair of "standard" blue trousers whitish for much washing, indeed a sharp contrast with the bell-bottom worn by that boy who was bearing a pitiful look on his face. Years later, I and the boy met and both of us couldn't help laughing at the teacher for her trying to suppress a kid's desire for being different. Indeed, boys in all schools were driven by instinct to eye pretty girls with curls on their hair or "fancifully" dressed. Even I, supposedly a "good" student, took pleasure in secretly viewing photos of Taiwan and mainland beauties while appearing prim and proper in public.

Beginning the 1980s, people became increasingly keen to colors and styles of their clothing, though in the eyes of today's young people, people of my generation looked rustic even with their best clothes on. Western suits, which had disappeared since the 1950s, were gaining popularity when I was a teenager. But many people wore them casually, the way they wore a T-shirt or pullover. Mother bought a cheap western dress for me after I entered the RUC – a jacket, a pair of trousers and a tie. It was too loose for me and would be wrinkled with untidy folds shortly after I put it on.

Women are always keen to fashion. In China, women in fact pioneered a change in styles of clothing in the 1980s. Increasing numbers of them became bold enough to wear clothes that would have been condemned as representing a "bourgeois way of life." Girls looked surpassingly charming with their colorful skirts fluttering in breeze. Taiwan and Hong Kong pop singers kept arriving, bringing with them mini-skirts, sunglasses and close-fitting clothes, which were to become popular on the mainland in a short time.

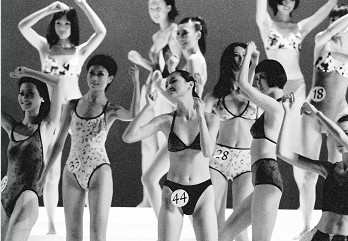

Fashion shows, which had been taboo, were appearing when I was studying at the RUC. I was working as an intern at Xinhua's Hubei Branch when I was assigned to cover an amateur fashion show on a lawn by Lake Donghu, a scenic spot in Wuhan, capital of Hubei Province. Fashions displayed there were quite rustic by today's standards, and the models wore a kind of stockings that had been out of fashion even in China. To tell the truth, I myself was conservative and I was quite shy when taking photos of those young women. But I was to get used to enjoying the beauty of models as I was assigned to cover more and more fashion shows, which had become quite commonplace by the early 1990s. The earliest fashion models in China were amateurish in performance compared with their counterparts of today. But they deserve our admiration for being bold enough to step onto the T-shaped stage and use their beauty to break the shackles of the traditional mentality and provide the public with a unique form of beauty to enjoy. Now that their country has become the world's greatest garment producer and exporter, the Chinese people are now free from a tradition that used to suppress their desire for things beautiful.

Beauty contests came along with fashion shows. In Beijing, people heard about "beauty contest" toward the late 1980s. I was undergoing internship at Xinhua's Photographic Department in Beijing in early 1988 when I learned that something called "Women's Youth and Vigor Contest" was to take place in town. I lost no time to find out what it was.

The "Women's Youth and Vigor Contest," so to speak, was to be held at the Cultural Center of Chongwen District. I stepped into a dimly-lit room inside the center, a lone structure on one side of a street, where women were queuing to get registered for participation. "What is it all about?" I asked a fellow photographer. "Call it 'beauty contest,'" he replied.

But I was still puzzled. "Why don't they call a spade a spade?" I asked. The guy whispered into my ears with a mysterious smile on his face: "They (the organizers) are afraid that a beauty contest will be frowned upon and that's why they call it 'women's youth and vigor contest.'" "Indeed clever, aren't they?" he added.

I had no idea of whether my photos of this contest would get the approval for release. There were so many restrictions on news reporting that a reporter had to weigh all the pros and cons before setting about covering a news event or a news person.

"Get the photos, anyway," I decided. Then I tried to strike a conversation with those young women. They were obviously nervous when I asked them why they wanted to participate. They just stared at me, too shy and frightened to speak, or hurried away. "Please don't name me in your reporting," one of them, who looked like a student, begged. "I'll be down if my parents know I am involved."

The applicants, according to the organizers, were workers, students, kindergarten teachers and restaurant waitresses, and most of them had come discreetly, without seeking the consent of their families or employers. They had to, as society remained conservative. Finally, I found one, a factory technician, who was willing to talk with me. She told me in all seriousness: "I want to improve my temperament and enhance my ability." The girl is still fresh in my mind, alive with her answer which I think was so good.

Not long afterward, the "contest" was called off. No reason was given but it was said that the authorities thought beauty contests were "improper" for the Chinese society.

Ten years afterward, I met Wei Xue, a contestant who had made her way into the finals before the contest was cancelled. She was then a student, and now she owned a PR company. "If the contest was not cancelled," she said, "I would have led a different life." Feeling that there was not much room in China for her development, she left for study abroad, first in Japan and then in the United States. She returned after completing her studies, upon discovery that China's economic achievements were providing an increasingly great potential for people like her to bring into full play their wisdom and talent. The company she started after she was back from abroad was "thriving," she told me.

Heavy cargo flights taking off

Heavy cargo flights taking off In pictures: PLA's digital equipment

In pictures: PLA's digital equipment  Americans mark Thanksgiving Day with parades

Americans mark Thanksgiving Day with parades Love searching stories in cities

Love searching stories in cities  Shanghai shrouded in heavy fog

Shanghai shrouded in heavy fog Office ladies receive ‘devil’ training in mud

Office ladies receive ‘devil’ training in mud Changes in Chinese dancing culture

Changes in Chinese dancing culture  Highlight of Mr Bodybuilding and Miss Bikini Contest

Highlight of Mr Bodybuilding and Miss Bikini Contest  Picturesque scenery of Huanglong, NW China

Picturesque scenery of Huanglong, NW China China's moon rover, lander

China's moon rover, lander Spring City Kunming witnesses snowfall

Spring City Kunming witnesses snowfall Citizens rush to buy cars

Citizens rush to buy cars  Life in an ancient academy

Life in an ancient academy Best photos of the week

Best photos of the week White-collars, black eyes

White-collars, black eyesDay|Week|Month