|

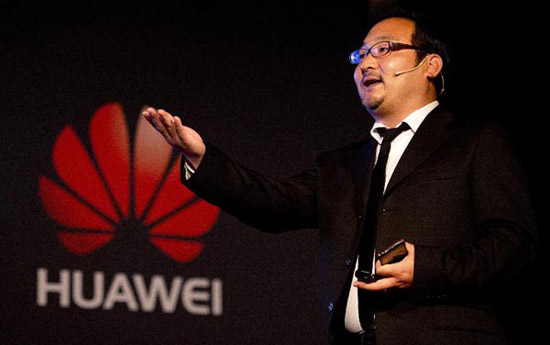

| Xin Wen, CEO of Huawei Technologies (The Netherlands), unveils the latest smart phone Ascend P1 in Amsterdam on Sept. 25, 2012. (Xinhua File Photo) |

Chinese companies are aggressively pushing for a bigger share in ASEAN's biggest communications market as it will have its dynamics swayed by new laws and the outcome of national elections set for 2014, reports Sudeshna Sarkar.

The town of Ubud in Bali may look like a sleepy idyll with its green, endless rice fields, emerald hills and the sacred monkey forest where lucky visitors may chance upon a chattering crab-eating macaque, but its entrepreneurs don't let grass grow under their feet.

By 10 am, Yasmin Robles has drawn up the shutters at Namus Ubud - her ice cream parlor, pizza place, coffee shop and, on bad weather days, a retreat from the scorching sun or pouring rain - ready for business. She has proclaimed the day's menu on her company's Facebook page for patrons to view and decide if they want to drop in for lunch.

"I use (Namus Ubud's) Facebook page to stay connected with my customers from other cities and abroad," the 38-year-old said. "And to inform local customers about my special products, events in Ubud, and sometimes, some words of wisdom."

She is not the only one to turn to social media to drive business. This land of 248 million people, the fourth most populated in the world, is also the second-largest user of Facebook and the fourth-largest user of Twitter.

By 2017, forecasts say mobile phone penetration will hit 173.5 percent with nearly 444.8 million subscribers in Indonesia, making it one of the largest markets in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations for mobile phone makers and equipment suppliers.

And Chinese companies are already present in Indonesia as "aggressive" sellers of information and communications technology products, vending to both fixed-line and cellular phone operators, said Juni Soehardjo, director, telecommunication, IT and media sector, at the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

The three major mobile phone operators are Telkomsel, the biggest with more than 100 million subscribers, Indosat with over 52 million users, and XL Axiata with approximately 45-50 million subscribers.

ZTE, which entered Indonesia in 1999 and has six regional offices besides its Jakarta headquarters, has been collaborating with all three, besides Telkom, which provides fixed lines and holds a majority stake in Telkomsel, and a host of other smaller operators.

The Chinese company takes pride in its green applications, which it said reduce power consumption by 90 percent and carbon emissions by 95 percent.

In April this year, China Telecom, China's biggest fixed-line operator, signed an agreement with Indonesian wireless-based services provider Smartfren Telecom to offer three months' network consulting services at Smartfren headquarters.

As part of the standard overseas expansion procedure, Chinese lender Industrial and Commercial Bank of China has ICBC (Indonesia), which works with companies like China Telecom and China Communications Services (Indonesia) in Jakarta to further Chinese enterprises' globalization bid.

"China-based companies have indeed increased their foothold within the country," said Sudev Bangah, associate research director and head of operations at market intelligence agency International Data Corporation Indonesia.

"Recent surveys have showed that recognition of companies such as Huawei and ZTE as a network hardware provider has increased in mindshare, (though they trail) behind the likes of (US multinational) Cisco."

History has been a deciding factor behind Chinese companies' presence in Indonesia, where about 3 to 4 percent of the population are said to be of Chinese origin.

"The 'investment' relationship between Indonesia and China dates historically for more than 50 years," Bangah added from his Jakarta office. "China is one of the top 10 foreign direct investors in Indonesia, trailing the likes of Japan, South Korea, Singapore, the US and the Netherlands.

"The interest in Indonesia essentially stems from the similarities between both countries in terms of their being driven heavily by domestic consumption, with large geographies and plenty of infrastructure development still required."

While the majority of China investments is seen as coming from State-owned enterprises from diversified sectors such as construction, manufacturing and resources, Bangah said Indonesia is definitely a key focus country for multinationals looking at expanding their market.

While not a gateway to ASEAN, unlike more geographically strategic nations such as Malaysia and Singapore - or even Vietnam to a certain extent - Indonesia, he said, is capitalized mostly for domestic consumption.

Despite the prevailing cultural link, cultural affinity would be a crucial element for Chinese telcos for greater presence, Bangah said.

"Indonesia is an archipelago with disparate culture and (language and time) differences from West to East. On top of that, local partnerships (which are already occurring) are one of the most crucial elements for Chinese telcos to consider when trying to penetrate the market."

ICCI's Juni said as Chinese telecom companies are considering profitability like any other foreign or domestic investor, and they have to keep several things in mind before entering the Indonesian market.

Since 1999, when Indonesia deregulated the telecom sector and ushered in sweeping reforms, ending monopoly and allowing private investment, the first ones to get off the ground and enter the archipelago have already been firmly entrenched. They include SingTel with over one-third stake in Telekomsel, Qatar Telecom, which holds majority shares in Indosat, and Malaysia's Axiata Group that too has a controlling share in XL Axiata.

"Indonesia already has more than 10 telecom operators, all of whom have a national license," Juni added. "It is highly unlikely that the government will issue an additional license for a new entrant."

Though Chinese companies can buy shares in existing players, the disadvantage is that major ones like Telkomsel and Indosat, though public companies, are under the Ministry of State-Owned Enterprises.

Bureaucratic red tape and possible corruption may be other deterrents for Chinese investors. But probably the greatest concerns are things that are yet unknown.

Juni said she feels the biggest regulation issues are the new broadcasting and telecommunication bills that will replace the existing Broadcasting Act and Telecom Act. The drafts are in parliament without any timeline given so far.

Then there is the politics factor. Next year Indonesia will hold general as well as presidential elections and the sector will have to wait and see how long the new ministers take to get acquainted with the technicalities and how they mold policies.

But these hurdles apart, Chinese companies, she said, are not regarded as security threats. "This can be seen from the majority of telecom companies that are currently using Chinese devices in Indonesia," she added.

China's weekly story (2013 6.22-6.28)

China's weekly story (2013 6.22-6.28)

![]()