A small probe could get to Mars in less time than it takes to watch 'Interstellar'.

That's according to physicist, Phillip Lubin, who recently outlined how a probe could reach the red planet in just three days.

Now, Lubin says that time could be reduced to just 30 minutes by using extremely powerful lasers to propel a wafer-thin unmanned spacecraft.

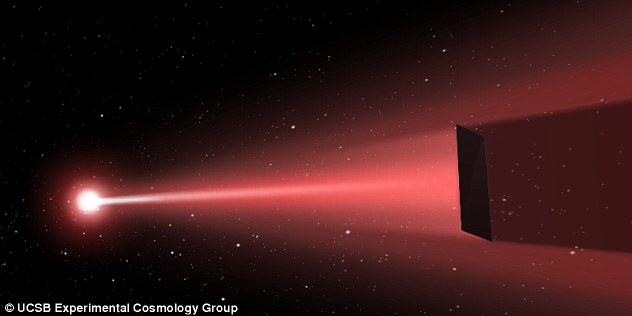

Physicists in California are working on spacecraft that could let humans reach the nearest stars in our solar system - a challenge that is not possible with current propulsion technology. The answer could lie in what's known as photonic propulsion, a technique that uses light from lasers to produce thrust (illustrated)

The UC Santa Barbara physics professor first unveiled his 'directed energy propulsion' concept at a Nasa Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) symposium last October.

He's now followed up his comments with a detailed 52-page paper in the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society.

He claims that by firing a laser at a spacecraft, it would have the ability to achieve frictionless acceleration in space.

That would allow it to reach a more than a quarter speed of light in just minutes.

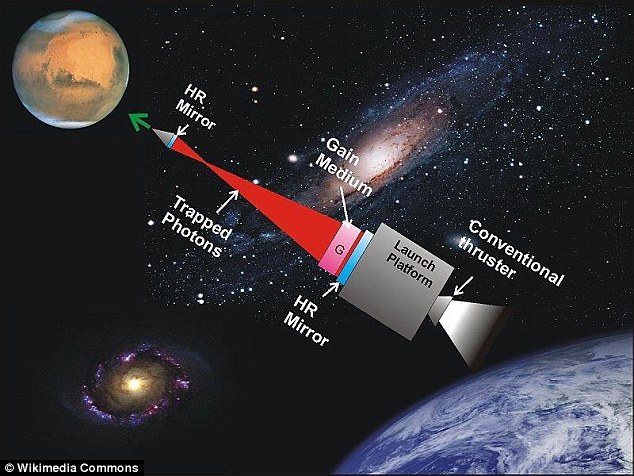

'As an example, on the eventual upper end, a full-scale (50-70 GW) DE-STAR 4 - Directed Energy System for Targeting of Asteroids and Exploration - will propel a wafer scale spacecraft with a one meter sail to about 26 percent the speed of light in about 10 minutes,' Lubin says.

'[It would] reach Mars (1 AU) in 30 minutes, pass Voyager 1 in less than 3 days, pass 1,000 AU in 12 days and reach Alpha Centauri in about 15 years.'

This means that the craft would be travelling at roughly 174.3 million miles per hour.

There are some major flaws in Lubin's plan, such as how such a fast-moving probe would slow down when it reached Mars.

The difficulty of encountering space junk is a major problem. But according to Lubin, the accumulation of interplanetary dust won't impact its speed.

Digital Trends points out that another problem may be the impact of 'time dilation'.

All spacecraft operate by firing propellant in the opposite direction to the way they want to travel. Traditionally this propellant is fuel. Photonic propulsion uses an array of lasers instead, which means no fuel needs to be carried on the spacecraft. This enables it to accelerate for longer and reach higher speeds (illustrated)

The effect was shown in Christopher Nolan's 2014 science film Interstellar, in which a group of astronauts fly into the center of a supernatural wormhole.

As they move farther into the universe, the time they experience slows down.

The same thing could happen to a crew if they were able to reach Mars in 30 minutes. While it would appear as if they only spent 30 minutes getting to the red planet, in reality decades would pass.

However, Lubin points out that manned probes are still a distant dream, and his proposal centres on a tiny unmanned craft.

Whereas things like warp drives remain a fantasy, Lubin says this technology is available right now, and it may be scalable.

'This technology is not science fiction,' Lubin says. 'Things have changed.'

Professor Phillip Lubin and his team from the University of California Santa Barbara are currently working on the Directed Energy Interstellar Precursors (Deep-In) programme.

One problem with the concept may be the impact of 'time dilation'. The effect was shown in Christopher Nolan's 2014 science film Interstellar, in which a group of astronauts fly into the center of a supernatural wormhole. As they move farther into the universe, the time they experience slows down.

The programme aims to create probes capable of reaching relativistic speeds and travelling to the nearest stars.

'We know how to get to relativistic speeds in the lab, we do it all the time,' said Lubin at Nasa's National Innovative Advanced Concepts (Niac) symposium.

'When we go to the macroscopic level, things like aircraft, cars, spacecraft, were pathetically slow.'

He claims with laser technology 'we could propel a 100kg aircraft to Mars in a few days. In comparison it would take a shuttle roughly a month to get there,' the researchers said.

Professor Lubin was making reference to Nasa's Space Launch System (SLS) shuttle.

By comparison, 'the SLS when it takes off will have a power of between 50 and 100GW to get into orbit,' said Professor Lubin.

When it's built in 2018, it will launch astronauts in the agency's Orion spacecraft on missions to an asteroid placed in lunar orbit, and eventually to Mars.

'It turns out to get to relativistic speeds, just using different technology, it would take the same amount of energy for roughly the same amount of time,' continued Professor Lubin.

Lubin, however, stressed that his current work is focused on small-scale probes.

'We are not proposing systems to send humans to interstellar distances,' he told DailyMail.com about the current project.

'Humans are extremely fragile and require a lot of support. Robotic missions are much better suited for interstellar exploration in the future.'

Day|Week

Train Attendant Recruitment Held in East China

Train Attendant Recruitment Held in East China In pics: Russia's Su-35 fighter jets

In pics: Russia's Su-35 fighter jets Young monks learn kungfu in NE China temple

Young monks learn kungfu in NE China temple Scenery of Guzhu, thousand-year-old ancient village in E China

Scenery of Guzhu, thousand-year-old ancient village in E China China releases HD true color images of lunar surface

China releases HD true color images of lunar surface To-be flight attendants undergo training at snow-covered field

To-be flight attendants undergo training at snow-covered field Aerial photos taken on J-11 fighter

Aerial photos taken on J-11 fighter 'Coldest town in China' — a fairyland you don't want to miss

'Coldest town in China' — a fairyland you don't want to miss Deep love for breathtaking Hainan

Deep love for breathtaking Hainan Beautiful Chinese tennis player Wang Qiang goes viral online

Beautiful Chinese tennis player Wang Qiang goes viral online