|

| Peter C. Espina/GT |

The EU today comes close to being a federal state, and in many fields, has its own constitutional order, laid down in treaties ratified by every member state. Never has any state left the union, but today two are on the brink of doing so, the UK and Greece.

Both of them feel obliged to comply with rules imposed on them by the EU, by its institutions, representing the whole range of member states, obligations they consider as unbearable.

Both of these countries were not among the founders, the UK did not want to, and joined only in 1973, and Greece was not in a state to join, because it was a military autocracy (and only democracies are allowed to become members), until it finally got rid of its military rulers and joined in 1981.

But the UK and Greece, if they leave, would do so for very different reasons.

The UK, first, has always been sceptical about the need to accept rules beyond the guarantee of free trade in the common area. A common political destiny of the European family of nations, freely joining together under the commonly accepted umbrella of a federal constitutional order, has always been a strange idea in the eyes of the British.

The realm of their historical experience has always been the oceans, not the European continent; their nation state was one of the very few that survived WWII with its integrity intact, whereas nearly all the others lost their trust in their state alone to provide them with the basic common goods of peace, freedom, and justice.

They are ready to go for common guarantees, which the Brits are much less willing. Meanwhile, the UK has always had specific ties beyond the Atlantic, with the US, and a particularly liberal approach to the international economy, whereas the continentals are much more inclined to impose rules, and indeed common law, on their markets.

All these differences amount, in the UK, to an ambiguous attitude toward the EU, with its law making political system and the administration, which goes along with legislation.

Staying with the EU is nevertheless considered to be much more advantageous to the British economy by economic actors; 80 percent of the people employed in the "City of London," the world's biggest financial market place, alongside New York, are convinced that the UK should not leave the EU.

The promise of the Conservative government headed by David Cameron is a bid that the EU will comply more with the British desire for less common rules and more individual (market) freedom, under the menace of the UK leaving.

This would be a dangerous gamble, since it could work out as a disaster for both sides, but certainly more on the British than on the European.

Greece is in quite a different situation.

First, the question is not whether it would leave the EU entirely. The question is limited to leaving the club of member states that share a common currency, the euro.

Greece, too, is not satisfied with rules imposed on it by the EU, but for nearly the opposite reasons to the UK - these rules are too neo-liberal, in the eyes of the government elected early this year, which is a radical left government, at the opposite of the neo-liberal British government.

Greece proved to be quite unable to bear the burden of the consequences of the financial and economic crisis in 2008/09.

All the EU member states have to extinguish the fire set in their economies, and societies, at the time by pouring huge sums of public money on it.

This move led them directly into unprecedented deficits and public debt. Some of them, most especially Greece, needed the financial help of the others to prevent them from state bankruptcy, a year or so later. And the others were and are ready to help - under one condition: Greece, as with Spain, Portugal, Ireland, and Cyprus, had to promise that it would improve its public finances, and comply with the rules imposed on behalf of the EU, in order to pay back its debt.

It is painful indeed to apply and push through these rules, since they work out, for many people, as a deep cut in their purchasing power and their social security.

A majority of Greeks voted for a political party, which promised to change these rules unilaterally - a populist promise, since such deals are convened by both sides.

The dilemma today is that the Greek government can avoid leaving the eurozone and creating a disastrous mess for their economy only by breaking its promises - whereas the other members of the euro are not willing to lose the credits they gave away, nor to renounce the implementation of the convened measures aiming at a sound budgetary policy.

The doors are still open for the UK and Greece - open for compromise, or open to leave.

There is a strong interest in the EU to hold the 28 nations together, in a world where giants arise and the Europeans, individually, prove to be dwarfs. And dwarfs they will be, both the UK and Greece, if they leave the secure haven of the EU.

Beautiful and smart - post-90s college teacher goes viral

Beautiful and smart - post-90s college teacher goes viral Students take graduation photos in ancient costumes

Students take graduation photos in ancient costumes Forbidden City collects evidence from nude photo shoot

Forbidden City collects evidence from nude photo shoot Chinese students learn Duanwu customs in Hefei, Anhui

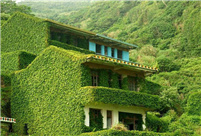

Chinese students learn Duanwu customs in Hefei, Anhui Abandoned village swallowed by nature

Abandoned village swallowed by nature Graduation: the time to show beauty in strength

Graduation: the time to show beauty in strength Top 16 Chinese cities with the best air quality in 2014

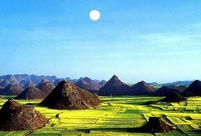

Top 16 Chinese cities with the best air quality in 2014 Mysterious “sky road” in Mount Dawagengzha

Mysterious “sky road” in Mount Dawagengzha Dragon boat race held to celebrate upcoming Duanwu Festival

Dragon boat race held to celebrate upcoming Duanwu Festival  Military parade to send message of peace

Military parade to send message of peace Dog lover rescues Yulin pups and cats

Dog lover rescues Yulin pups and cats FAW strives to develop its own line of vehicles

FAW strives to develop its own line of vehicles African legal professionals study in China due to closer business ties

African legal professionals study in China due to closer business tiesDay|Week