Chinese PLA Navy in marine security exercise in Jervis Bay

Chinese PLA Navy in marine security exercise in Jervis Bay

Official name of giant panda cub 'Yuanzai' to be announced

Official name of giant panda cub 'Yuanzai' to be announced

Communication ship Yuri Ivanov launched in Russia

Communication ship Yuri Ivanov launched in Russia

'Warriors' welcome tourists in Yue Fei Temple during National Day holiday

'Warriors' welcome tourists in Yue Fei Temple during National Day holiday

Shanghai Free Trade Zone begins operation

Shanghai Free Trade Zone begins operation

Grand parade of international carnival held in S China

Grand parade of international carnival held in S China

|

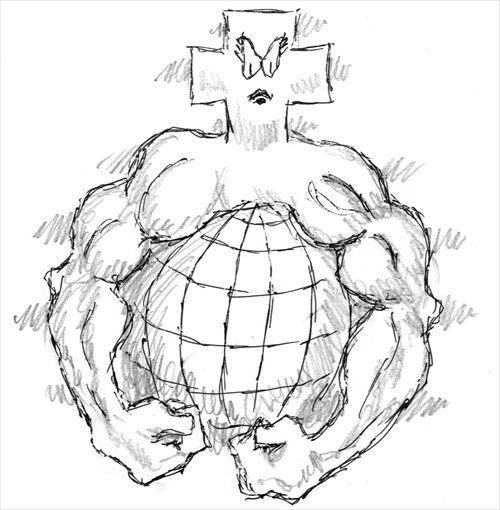

| (Illustration:GT/Peter C. Espina) |

Several photos that recently went viral on Weibo, or China's Twitter-like microblog, showing a girl drinking from a jug instead of a cup and another trimming her toenails with an awe-inspiring pair of pliers rather than a clipper, have drawn attention to the rising demographic of nühanzi, or manly women.

In a bid to redefine the word "female" in China, these "tough Chinese girls" are pointing us back to the periodic table. Given that "fe" represents "iron" - "female" could translate to "iron male" or someone manlier than a man himself, they argue.

Yet before you go labeling yourself a nühanzi, there is a list of criteria that you must first meet. If you never wear makeup, always carry your own bags, have no time to waste on "selfies" and annihilate potato chips by pouring them straight into your mouth from the bag - then congratulations, you are a strong contender.

But, to be a true-blue "iron female," you must devote nearly all of your waking hours to playing online games like Warcraft and League of Legends.

"Girl power" has been developing around the world for years, especially in developed countries. In China, the trend has become more prominent in recent years as the country's socioeconomic conditions continue to improve and advance.

Though that hardly means all working women today qualify as nühanzi, the sight of independent women around us has become commonplace in China, particularly in big Chinese cities like Beijing and Shanghai.

From high-salaried women who pay their own mortgage to those who run after the bus in high heels on their way to the office, it is evident that a greater number of women are taking control of their lives and solving problems on their own - without the help of men.

Often targeting the urban, educated female audience, Chinese movies, too, are more and more catering to nühanzi-types. In the romantic comedy I Do, released in time for Valentine's Day last year, the leading female role, Tang Wei, a 32-year-old shengnü or "leftover woman" played by famous actress Li Bingbing, is depicted as some kind of modern nühanzi-like goddess rather than a pathetic, old spinster.

With a successful career and her own apartment - and a defiant and decisive personality to match - she is the typical nühanzi - only with two billionaires chasing after her. One pretends to be an ordinary man and gradually works his way into her life, while the other, her ex-boyfriend, tries to win her back after breaking her heart.

In the end, all nice and coy, she turns them down - wanting them to compete again for her heart. The last scene shows the men clumsily running after her as she struts ahead with spectacular ease, her long, luscious locks bouncing playfully in the wind. I can still hear the laughter of the women at the theater when I think back to the movie's ending.

Yet for all the independence women are gaining, traditional values in the home are still far from being overturned.

Nühanzi are clashing with the men around them. Several of my girlfriends who have attended matchmaking parties complain that the men they meet still need and desire "traditional women" who focus on family and center their lives around their husband and child.

But nühanzi wouldn't be nühanzi if they couldn't handle a bit of a challenge, right?

It may take some time for all "manly men" to warm to China's emerging class of nühanzi - but their power to inspire is hardly being so foolishly overlooked.

Nühanzi pop singer Li Yuchun, who won over audiences in Super Girl's 2005 season with her boyish charm before splashing the cover of Time Asia magazine for courageously challenging traditional norms, continues to inspire a new generation of Chinese girls, encouraging them to believe that they can do anything that a man can do - and more.

National Plug In Day celebrated in Washington D.C.

National Plug In Day celebrated in Washington D.C. New model of indigenous surface-to-air missiles testfired

New model of indigenous surface-to-air missiles testfired  118.28-carat diamond to be auctioned in HK

118.28-carat diamond to be auctioned in HK Heart melting! Adorable panda cubs shown public

Heart melting! Adorable panda cubs shown public Naked foreign student sits in the middle of a road in Haikou

Naked foreign student sits in the middle of a road in Haikou  Colorful Yunnan: Enjoy the natural beauty

Colorful Yunnan: Enjoy the natural beauty Harbin named Chinese city with most beautiful women

Harbin named Chinese city with most beautiful women For last four students, teacher couple sticks to post on island

For last four students, teacher couple sticks to post on island  When big sport stars were kids

When big sport stars were kids PLA's 38th Group Army conduct training

PLA's 38th Group Army conduct training People mourn for victims of mall attack

People mourn for victims of mall attack Documentary of Chinese female construction workers

Documentary of Chinese female construction workers Li Na vs Novak Djokovic in charity match before 2013 China Open

Li Na vs Novak Djokovic in charity match before 2013 China Open Travel with photographer- Gansu province

Travel with photographer- Gansu province American batman soars through China's Jianglang Mountain

American batman soars through China's Jianglang MountainDay|Week|Month