|

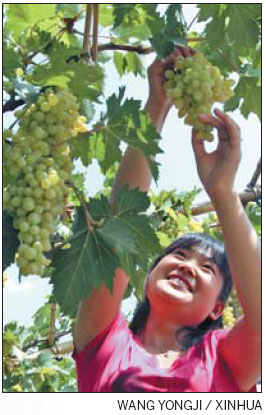

| A woman living near the Inner Mongolia's Kubuqi Desert picks grapes for a local vineyard.(Xinhua) |

In 2008, the vineyard piloted the method of growing grapes and alfalfa on the same ridge.

Alfalfa proved to be the fragile grapevines' effective guardian. The herb typically lives 5-7 years, providing grapevines time to grow strong enough to survive sandstorms. Alfalfa stalks are buried to enhance fertility.

"You must respect nature's rules," Li says.

"If you cheat soil, it cheats you back. Using scientific approaches to adapt can best reap nature's rewards."

Alfalfa's rewards are the rich nitrogen it gives soil and the nutrition it offers sheep. Sheep have long been a staple of the area's largely nomadic herding economy.

The vineyard produces 100 tons of alfalfa annually in addition to 500 tons of grapes. The alfalfa is sent to a sheep farm 100 km away and returns as manure that fertilizes organic grapes.

The vineyard is set to expand its claim on the desert, with a 13-hectare poplar and pagoda tree nursery.

This not only improves the local environment but also provides economic opportunities to migrants driven off their land by ecological hardships.

Chen Huizi, a native of Qingyang, Gansu province, struggled with unstable corn yields in her dry and marginally arable hometown.

She came to the vineyard in 2008 and trained to become a grape farmer.

"We used to depend entirely on nature's mercy," she recalls while pruning a vine.

"A stable salary is a blessing."

This small self-sustaining ecosystem has been replicated in three larger vineyards with similar habitats west of Wuhai, in neighboring Ordos and in the Ningxia Hui autonomous region's Wuzhong. The model now covers more than 6,600 hectares.

Inner Mongolia University biology professor and Hansen's cultural director Xue Xiaoxian explains: "The word 'chateau' is usually misunderstood. People usually think of a castle with cellars. Instead, it's an essential form of agriculture."

Chateau's Chinese translation - jiuzhuang - literally means "wine manor".

"This is a carbon-reduction industry that's one step ahead of the low-carbon model," Xue says.

"Grapes are a long-term investment. We've just begun to see results."

This progress encourages Chinese winemakers long frustrated with the country's inability to produce internationally acclaimed wines.

"Chinese wine is neglected in overseas markets because its production bases lack unique characteristics," says winemaker Kang Dengzhao, who's also chief technical engineer of the winery in Hansen.

"Wineries often collect grapes from individual growers, making it difficult to stick to a single standard. Sometimes the more grapes are grown, the poorer the quality.

"But our desert grapes are distinctive."

Turn white rabbit to 'gold' - A young entrepreneur's goal

Turn white rabbit to 'gold' - A young entrepreneur's goal

![]()