Harbin Int'l Ice and Snow Festival opens

Harbin Int'l Ice and Snow Festival opens 'Jin' named the word of the year by cross-strait netizens

'Jin' named the word of the year by cross-strait netizens Chinese scientific expedition goes to build new Antarctica station

Chinese scientific expedition goes to build new Antarctica station

Chinese naval escort fleet conducts replenishment in Indian Ocean

Chinese naval escort fleet conducts replenishment in Indian Ocean 17th joint patrol of Mekong River to start

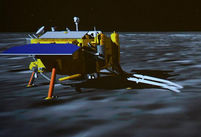

17th joint patrol of Mekong River to start China's moon rover, lander photograph each other

China's moon rover, lander photograph each other Teaming up against polluters

Teaming up against polluters

|

| Alan M. Jacobs, Associate Professor of Political Science, University of British Columbia. (File Photo) |

It is commonly argued that democracy is a political arrangement that is poorly equipped to manage the future. In order to win elections, it is said, politicians in a democracy routinely bribe voters with short-term tax cuts and government handouts, ignore the long-run costs of their actions, and leave the toughest policy problems for their successors to solve. Democratic citizens, it is said, only encourage this kind of short-sighted behavior. The typical voter, so goes the folk wisdom, has just one question for her government at election time: “What have you done for me lately?” And so, in a democracy, the can is always being kicked down the road.

If we think about some of the greatest long-run policy challenges facing Western democracies, there appears to be some truth to this cynical view. Consider the looming catastrophe of climate change; dwindling stocks of oil and other natural resources; crumbling roads, bridges, and other vital infrastructure; the growing financial burden of aging populations; and the fiscal sustainability of the state.

In the face of these long-term quandaries, Western governments have, on the whole, done much less than they should. For instance, OECD governments’ capital budgets are in the midst of a 20-year decline, vital road, rail, water, and power-transmission systems await trillions of dollars in needed repairs.

Despite decades of warnings from climate scientists, industrialized countries have allowed carbon concentrations in the atmosphere to rise to perilous levels. From the oil sands of Alberta to the shale formations of West Virginia, governments across North America scramble to extract every last ounce of fossil fuel from the ground beneath them – while clean, renewable energy sources make up a tiny fraction of energy production in OECD countries.

And many rich democracies have yet to squarely confront the dilemma of demographic change. At best, their governments have simply cut back on state pension benefits, leaving today’s workers at severe risk of retiring in poverty decades from now. Meanwhile, many European countries – from Greece to Italy – have built up unsustainable levels of public debt, leaving tomorrow’s workers with an enormous tax bill.

It is tempting to conclude that democratic politics is inherently myopic, incapable of grappling with the long term and investing in the future.

Tempting, but wrong. If we look more carefully at the policy performance of contemporary democracies, we in fact see enormous diversity. Rather than uniform short-termism, we see wide variation in the degree to which governments invest in the long term.

When it comes to infrastructure, for instance, some elected governments invest far more than others. While Austria spent a paltry 1 percent of GDP on infrastructure in recent years, Korea’s government has invested a whopping 5.2 percent of national income on capital projects.

Likewise, in climate change: while many countries have failed to take serious action on carbon, others have taken difficult steps to put a price on carbon – some, by setting up emissions-trading markets (as in the European Union, Quebec, New England, and California) and others by imposing carbon taxes (as in Australia and British Columbia). At the same time, investment in wind, solar, and other renewables has skyrocketed across the OECD over the last decade.

Chinese Consulate General in S.F. burned for arson attack

Chinese Consulate General in S.F. burned for arson attack Roar of J-15 fighter is melody for operator on the Liaoning

Roar of J-15 fighter is melody for operator on the Liaoning A 90-year-old forester's four decades

A 90-year-old forester's four decades Most touching moments in 2013

Most touching moments in 2013 2013: Joys and sorrows of world politicians

2013: Joys and sorrows of world politicians Missile destroyer Zhengzhou commissioned to Chinese navy

Missile destroyer Zhengzhou commissioned to Chinese navy China is technically ready to explore Mars

China is technically ready to explore Mars Photo story: Life changed by mobile technology

Photo story: Life changed by mobile technology Bullet train attendants' Christmas Eve

Bullet train attendants' Christmas Eve Cradle of high-speed train CRH380A

Cradle of high-speed train CRH380A  'Red Army' division conducts winter training in N China

'Red Army' division conducts winter training in N China  Classic scenes come to life

Classic scenes come to life Harbin Int'l Ice and Snow Festival opens

Harbin Int'l Ice and Snow Festival opens  Cindy attends commercial event with her parents

Cindy attends commercial event with her parents Get to know China's national pole dancing team

Get to know China's national pole dancing teamDay|Week|Month